Dyer Lum on the Civil and Mormon Wars

The present struggle between the South and North is, therefore, nothing but a struggle between two social systems, the system of slavery and the system of free labour. The struggle has broken out because the two systems can no longer live peacefully side by side on the North American continent. It can only be ended by the victory of one system or the other.

The Civil War in the United States (1861)

“Where then is the remedy? Politics offers none. Our political state is based on the present economic condition of things.”

Civil War

Slavery becomes non-conducive to capitalism. Slave ownership is a large and fixed investment which is unsuitable to quickly changing industrial markets. During economic downturns it is less expensive to fire a worker than to sell a slave. And as industry expands, even the slave-owning agricultural sectors of an economy begin to conflict with the interests of capitalists. Slave owners hold a substantial portion of the labour force off of the labour market reducing competition for jobs and forcing capitalists to pay higher wages than would be the case if slaves' labour power were available on the market. What capitalists want is as much unemployed but available labour at their disposal as possible (without causing riots) — that, and labourers who are responsible for housing and feeding themselves.

That is why at the rise of capitalism in Europe serfdom was abolished, the commons were enclosed to force the peasants off of their land (and their means of subsistence), and finally harsh vagrancy laws and forced-labour workhouses were established to coerce the first wage workers into the factories. And that is why, in the United States during the 19th century, the industrial North increasingly came into conflict with the slave-owning South. The war eventually crushed the slaveholders' economy and established wage work as the basis of capitalism throughout the Union while providing former slaves' labour power to the labour market as free workers.

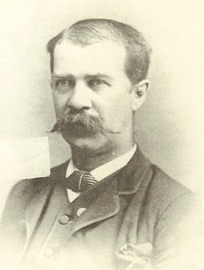

One of the early writers to give such an economic theory of the forces which lead to the American Civil War was Dyer Lum (1839 – 1893) who became an influential anarchist and labor activist toward the end of the 19th-century. Writing in 1886 he said of the capitalist North and the agrarian-slavery South, “They were rival industrial systems which had met in the same path, and one must give way. The war followed.”[1] Lum, eager to do his part in ending slavery, volunteered for and served the Union forces for three years. But upon observing the way the South was re-integrated into the union after the war in terms favorable to speculators, military contractors, and monopolists, he had second thoughts about the ultimate purpose of the war.

To-day, South and North alike admit the fundamental principle of our industrial system, the corner stone of our economic structure: Free labor is cheaper than slave labor! Employers without responsibilities could find new fields for enterprise when the system which entailed responsibilities was once removed. The South are converted; the poverty of a factory population is no longer an Eastern peculiarity. The gray meets blue in hearty union to draw dividends and cut coupons. They have found free labor the cheapest. (88)

Mormon Wars

Just as the Civil War had brought the South into alignment with the capitalist system of wage labour, Lum saw the Federal repression of the Mormons in Utah as an attempt to undo the cooperative-based economy the Mormons had established in order to expose them to the exploitation of the industrial East. It was for the expansion of capitalism, Lum wrote, “that the cry has gone forth that the Mormon must go!”

Lum, who traveled to Utah as part of a congressional committee on labor issues, had a very high regard for Mormon society. In one of his booklets he wrote, “The whole Mormon system, social, religious, industrial, is essentially based on two fundamental principles: cooperation in business and arbitration in disputes” (which he contrasted to the mainstream American values of capitalism and civil litigation).[2] He was so enamored with their cooperative businesses that he viewed Utah as perhaps the most successful socialist country anywhere: “The living question of the present is that stated in the preamble of the constitution of the Knights of Labor as ‘the abolishment of the wage system,’ a problem the Mormon alone has solved.” (86)

Lum was writing at a time when the United States government was taking advantage of American bigotry toward Mormons and polygamy in order to pass legislation aimed at dismantling the Mormon society. The Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act of 1882 disenfranchised Mormons and put many of their leaders in jail while the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887 disincorporated the LDS Church, seized its property, and replaced Utah judges with federally-appointed judges.

But the war against Mormons began before the Civil War. In the 1830s, not long after Joseph Smith founded his church, Mormons began settling in Missouri. They did not find many friends among their new neighbors. Not only were the Mormon immigrants vocally against slavery (in a slave-holding state), but they voted. At one polling place in 1838, around 200 non-Mormon Missourians gathered to prevent Mormons from voting. The Mormons asserted their rights, and a brawl broke out. The skirmish at the polls was the first violence in a series of minor armed conflicts and raids that took place between Mormons and Missourians known as the 1838 Mormon War.

On October 27, 1838, the governor of Missouri, Lilburn Boggs, issued Executive Order 44, which has become known as the Extermination Order. The order read in part:

The Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description.

The Mormons (around 10,000 of them) were expelled from Missouri and found refuge in Illinois (and then eventually in the Utah Territory). While they were chased out of Missouri for threatening the slave economy there, they were also nearly chased out of Utah for threatening the expansion of capitalism.

In 1857-1858, President James Buchanan sent thousands of US troops to invade the Utah Territory in what has been called the Mormon War. The Nauvoo Legion, the Mormon’s militia, activated and held the Federal troops at the border (in what is now Wyoming) where both armies made winter camp.

Of course the Mormons knew that if the Federal troops were intent on entering Utah, they could not be held off for long. Brigham Young wanted to avoid any open fighting if possible. So in March of 1858 he began executing an evacuation plan. In northern Utah (including Salt Lake City), Mormons buried the foundation of the temple they were constructing, put kindling to their buildings, and as many as 30,000 fled southward leaving only enough men behind to set fire to everything in case the Army entered the territory.

When it became clear that the Mormons would rather burn their territory than give up their mode of living, a peace accord was reached with the federal government. The terms of the agreement allowed the Mormons to return to their homes and continue living unmolested, and in return Young was replaced as governor of the territory and the Army was allowed to enter and maintain a remote fort. Federal troops remained in Utah until they were withdrawn to fight the Civil War in 1862.

But against the renewed persecution of the 1880s, of which Lum and other American anarchists wrote, the Mormons were not as victorious. In 1890 the LDS Church capitulated and renounced polygamy; in 1896 Utah joined the Union as the 45th state and became increasingly integrated into the capitalist economy. The hierarchical structure of the Church fit well with capitalism and became a weapon against the more democratic elements of its priesthood.

The church today owns significant for-profit (non-cooperative) property, including businesses which employ church members (who also pay tithes). Some of the profits from church investments pay the salaries of the General Authorities (high-ranking leaders) who are themselves often property owners, executives, and/or well-paid professionals before accepting the church position. Meanwhile the rank-and-file members and third-world converts must work for a living. The church still inculcates mutual aid and relief societies (it is rare to find a truly destitute Mormon), but nobody today would mistake Utah for a great socialist country. In that sense it can be said that the Mormon War was eventually successful in defeating Mormonism.

The War on Fundamentalist Mormonism

I agree with Lum that the 19th-century Mormon economy in Utah was a barrier to Eastern capitalism, but I think Lum’s account is overly optimistic, especially his claim that the Mormon cooperatives had managed to abolish wage labour. As Leonard Arrington pointed out in his celebrated economic history of the Mormons in Utah, the Mormon principle of cooperation often meant class collaboration — Mormon capitalists and workers uniting against Eastern capitalists — rather than the class antagonism of socialist cooperatives.[3]

The Mormon social experiment — which sought not the abolition of capital but the cooperation between the owning and working classes (including state-ownership and central planning of some industries), strove for economic self-sufficiency, looked to a single almost supreme prophet for guidance, believed it was restoring ancient order to a decadent society, and cultivated a strong identity as a unified people in the face of external threats — shared some features of the Fascist movements which later arose out of radical unions in Europe.

Of course the LDS Church is also built on principles which would be impossible to reconcile with anything like Fascism, especially its cosmopolitan missionary program by which the church since its inception has made friends and converts from nations and in countries all over the planet. But suppose the church stopped proselytizing: what would an insular Mormon church look like, especially if its authoritarian elements were emphasized? We don’t have to imagine. The American West is dotted by isolated fundamentalist Mormon communities which split with (or were excommunicated by) the LDS Church beginning in the first years of the 20th century and have refused to this day to integrate into the mainstream society or economy. The largest organized group of fundamentalist Mormons is the “Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints” (FLDS) which is infamously characterized by authoritarian rulers, revered (or at least accepted) as prophets, who sexually abuse and economically exploit their subjects.[4]

Governments have used the crimes of those leaders to punish and attempt to dissolve FLDS communes in order to integrate members into society at large as taxable worker-shoppers. A series of raids culminating in a large 1953 action against the town of Short Creek (which is today the twin towns of Colorado City and Hildale) carried out by Arizona state troopers and national guardsmen resulted in the arrest of 400 Mormon men, women, and children. Some children were never reunited with their families, and the fact that most of the families were allowed to return home was only because of the immense nation-wide public outrage at the raid and the way it was carried out.

Again in 2008, acting on a false report of sexual abuse made via telephone by a non-Mormon woman in a different state, militarized police raided an FLDS compound in Texas. The police removed 462 children under the age of 18 and placed them in protective custody. The children were kept in custody for a month until an appeals court ordered that they be returned to their families. In 2012 the state of Texas initiated legal forfeiture and seizure proceedings against the ranch, a move reminiscent of the old Edmunds–Tucker Act, and in 2014 the State took physical possession of the property.

While fundamentalist Mormonism is not nearly as sympathetic as the Mormon society Dyer Lum knew and described, the retreat fundamentalist Mormons have made to insular authoritarianism is a direct result of the 19th-century campaign of state repression, a campaign which continues today.

Further Reading

Mormon Anarchism - Some Links is a list I maintain of links to Web resources pertaining to Mormon anarchism.

Arrington, Leonard J. Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-Day Saints, 1830-1900. New edition. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Lum, Dyer D. Social problems of today: or, the Mormon question in its economic aspects. New York: D. D. Lum & Co, 1886.

McCormick, John S. “An Anarchist Defends the Mormons: The Case of Dyer D. Lum.” Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (1976): 156-69.

Rockman, Seth. “The Future of Civil War Era Studies: Slavery and Capitalism.” A survey of works exploring the relationship between slavery and capitalism leading up to the Civil War from the Journal of the Civil War Era.