A Look At Bernie Sanders' Electoral Socialism

Bernie v. Debs: The Confusing Terminology of a Self-Avowed Socialist

Band-aids don’t fix bullet holes

The presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders, the formerly-independent senator from Vermont, has already accomplished what seemed impossible: it has further confused the American people about the meaning of socialism.

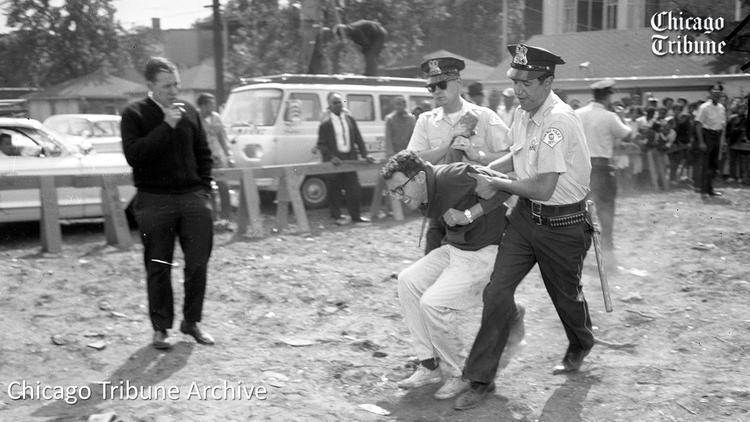

Sanders has consistently referred to himself as a "democratic socialist" for decades. While he was a student at the Univeristy of Chicago (1960-1964) his reading included works by Jefferson, Lincoln, Fromm, Dewey, Debs, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Freud, and Reich.[1] Though his writings reflect a greater influence by Freud and Reich than Debs and Marx, the mere fact that he’s read Marx and knows of Eugene V. Debs almost makes Sanders a revolutionary leftist by contemporary American standards. In 1979, disappointed that many of the students he spoke with had never heard of Debs, Sanders wrote and produced a 30-minute narrated film on his life and ideas.

The Debs video was so successful that Sanders considered producing “a video series on other American radicals — Mother Jones, Emma Goldman, Paul Robeson, and other extraordinary Americans who most young people have never heard of.” Unfortunately he never did.[2]

Bernie’s first involvement in electoral politics came in 1971 when he stopped by a meeting of the Liberty Union Party in Vermont and got nominated as the party’s candidate for an upcoming Senate special election. (Today the Liberty Party is so disappointed in his foreign policy that they have an article linked to the top of their website which refers to him as “Bernie the Bomber.”)

America has been a hostile environment to anyone and anything associated with the S-word during Sanders' entire political career, but he has still had impressive success at electoral politics as a self-avowed socialist in Vermont. When he ran for a fourth term as the mayor of Burlington in 1987, the Democratic and Republican Parties finally decided to join forces and run a single candidate against him. Sanders still won (as did his third-party successor, Peter Clavelle, who beat a joint Democratic-Republican candidate in the 1989 election).[3] Even as a senator he still considers Eugene Debs to be a hero of his, and he even at one point had (maybe still has) a plaque commemorating Debs hanging on the wall in his Washington office.[4]

Sanders did not shy away from the “socialist” label during his 2016 presidential campaign, and it has continued to galvanize both his supporters and detractors during his current campaign. But his “socialism” is very tame. He seems to welcome every interview as a chance to emphasize to the American people that his democratic socialism is nothing scary or radical.[5] He has always been indirect but clear that what he means by “democratic socialism” amounts to what is more commonly today called “social democracy.” But when discussing contemporary political ideas in English, it is generally important not to confuse “democratic socialism” with “social democracy.” As goals, they have come to mean nearly opposite things.

“Democratic socialism” is used to describe a broad range of approaches which emphasize a bottom-up and peaceful eradication of capitalist ownership and transition to a socialist economy (whatever that might look like). It is sometimes contrasted to Marxism-Leninism and other revolutionary schools which make less of a pretense of using or preserving liberal democratic institutions.

In contrast, “social democracy” usually refers to social and economic reforms which seek a more humane and democratically-controlled capitalist economy. It has come to be almost synonymous with the policies put in place by the Nordic states during the 20th century. In Sanders' terminology, it aims to curtail the excessive political and economic power currently enjoyed by America’s “billionaire class” in order to restore and maintain a healthy “middle class” supported by a Scandinavian-style welfare system.

But the two terms have not always referred to distinct ideas; a hundred years ago they were used interchangeably. And even while social democracy today doesn’t challenge capitalism, its reforms did grow out of the broad socialist and labor movements of the 19th century. One of the early theorists of social democracy was a German Marxist named Eduard Bernstein who became influenced by the British parliamentarian socialists of the Fabian Society. Bernstein argued at the turn of the 20th century that capitalism was capable of adapting and reforming itself to provide workers with rights and prosperity so that its collapse was avoidable and its extralegal overthrow was unnecessary. One of Bernstein’s most famous pronouncements is: “The final aim of socialism, whatever it may be, means nothing to me; it is the movement itself which is everything.”

Rosa Luxemburg, another German theorist, provided a defense of orthodox Marxism against Bernstein’s reformism as Reform or Revolution? (1900). In language which could be directed at a Sanders-style social democrat today, Luxemburg noted that reforms must be made in relation to a goal, so to divorce the socialist goal from social reforms is to abandon socialism itself:

[P]eople who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place and in contradistinction to the conquest of political power and social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal. Our program becomes not the realization of socialism, but the reform of capitalism; not the suppression of the wage labor system but the diminution of exploitation, that is, the suppression of the abuses of capitalism instead of suppression of capitalism itself.

While Sanders' use of “democratic socialism” to refer to mere reforms of capitalism is confusing in its anachronism, it is not without precedent. And there is a specific thread of American socialism that is almost continuous with Sanders' presidential bid and which provides some historic context to help understand the movement building around Sanders.

The short version of that history begins in the late 1950s with a man named Michael Harrington who is today most famous for his 1962 book on poverty (The Other America). Harrington was something of a protégé to Max Shachtman, a long-time member of the American socialist scene and an associate of Leon Trotsky. In 1958 Shachtman and his followers joined the Socialist Party of America (the party which was founded by Eugene Debs back in the day). Shachtman and Harrington argued that the Socialist Party was so small that it should adopt a strategy of “realignment”: focusing its energy on joining and realigning the Democratic Party to the left, including voting for and otherwise supporting the Democratic presidential nominees. Since workers weren’t going to the socialists, they said, the socialists should go to the workers. Harrington thought the New Left arising on American campuses could be the beginning “not of a ‘third’ party of protest, but of a real, second party of the people,” and that the Democratic Party could be transformed to that end.[6]

Harrington became a leader of the youth wing of the Socialist Party, the Young People’s Socialist League (YPSL). Significantly, not long after Harrington’s realignment movement became influential, a young university student and civil rights activist named Bernie Sanders joined the Chicago chapter of YPSL.

Disagreement over the realignment strategy contributed to several schisms of the Socialist Party of America in the early 1970s. Harrington resigned and founded the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee (DSOC) which endorsed the 1972 Democratic candidate George McGovern for president and continued to try to develop a socialist program within the Democratic Party. In 1982 DSOC joined with another democratic socialist group to become the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA).

I’m not sure if Sanders was directly or consciously influenced by the Shachtman-Harrington realignment caucus back in the '60s, but the movement ignited around his 2016 and 2020 campaigns for the Democratic presidential nomination is the most successful expression to date of that strategy.

The DSA still exists today. They were one of the few socialist organizations to enthusiastically rally behind Sanders in 2016, and his campaign has revitalized the organization.

In November 2015 Sanders gave an hour-long speech at Georgetown University to elucidate his meaning. The whole speech including this bit toward the end exemplifies the confusing way he uses the term socialist to mean something very much like capitalist:

The next time you hear me attacked as a socialist — like tomorrow — remember this: I don’t believe government should take over the grocery store down the street or own the means of production, but I do believe that the middle class and the working families of this country who produce the wealth of this country deserve a decent standard of living and that their incomes should go up, not down. I do believe in private companies that thrive and invest and grow in America.

For all of his talk about “socialism,” Sanders talks about raising wages and not about abolishing wage labour; about a government-guaranteed job and not about a life beyond wage work; about increased representation within the ruling class’s government and not about abolishing the ruling class. He manages to identify working families as the creators of wealth (though without mention of the non-American families who create so much of our wealth), but he never questions the fundamental mechanisms by which that wealth ends up in the hands of employers and bankers. As the editors of Jacobin magazine summarized his speech, “In short, for Sanders, democratic socialism means New Deal liberalism” (“The Socialism of Bernie Sanders”).

There is a persistent and widespread misconception which holds that an essential element of socialism is either government control of business or/and it is government funding of services. When Sanders promotes the latter by contrasting it to the former, he manages to reinforce both misconceptions simultaneously. The effect of such a shallow understanding is that the popular definitions of socialism make almost no useful distinctions and socialism talk in America consists almost entirely of debating various forms of capitalist policy.

It is argued by some pragmatic bandwagoners that labels are unimportant and whether we call Sanders a democratic socialist or a social democrat it’s his message and the movement he is building which are important. Others tack the opposite way: they say the referent is unimportant and we should just be happy someone is finally talking about socialism seriously and positively on TV.

Both views show a rather severe under-appreciation for the importance of radical rhetoric. It is when making modest, mundane reforms that it is most important to keep long-term radical goals in mind; without linguistic reminders, projects will inevitably lose themselves to the prevailing ideology. Likewise, to obscure the radical meaning of socialism as Sanders has done is to cut loose those rhetorical anchors and risk losing any transformative potential of his program.

Untangling the various meanings and histories of socialism to detail its useful distinctions and critiques is beyond the scope of this article. But it is worth pointing out, contra Sanders, that some socialists (even those so wary of being mistaken for Bolsheviks that they insert the redundant “democratic” modifier everywhere) still think socialism is supposed to be radical and maybe a little bit scary. The main point of departure between socialists and other reformers is that socialists, historically, have tended to be, you know, anti-capitalist in their rhetoric and projects. That may seem obvious, but it is a point apparently lost on Sanders and many of his young “socialist” supporters. An idea of what it means to be (and to not be) anti-capitalist can be had by comparing the rhetoric of Sanders with that of his hero Debs:

-

Sanders talks about the “billionaire class” and the “middle class,” or about the “1%” and the “99%”. Debs talked about the “capitalist class” and the “working class”; about the “master class” and the “exploited class.” The class analysis of socialists like Debs has the advantage that it is based on a clearly defined relationship to production rather than on arbitrary levels of income. One points to the symptoms; the other both explains the symptoms and points to the disease.

-

Sanders talks about increasing wages for the middle class. Debs talked about wages as slavery and worked to abolish the wage system.

-

Sanders talks about protecting American jobs, wages, and profits even at the expense of the global poor. In one interview last year he described open borders as a “right-wing proposal” which “would make everybody in America poorer.”[7] Debs talked about a world-wide revolutionary movement and said “I have no country to fight for; my country is the earth; I am a citizen of the world.”

-

Sanders says the USA should be a leader, but not a unilateral actor except as a last resort, in military conflicts. Debs opposed all war and empire. In 1918 he delivered a speech against World War I for which he was arrested and sentenced to ten years in prison (of which he served three).

-

Sanders is seeking the nomination of one of the most powerful capitalist political parties in the history of the world. Debs founded independent parties to challenge the monopoly held by the Republican and Democratic parties of his time. While he was in prison in 1920 he ran for president as the Socialist Party candidate and received nearly a million votes (about 3.4% of the popular vote).

I know it is not fair to measure any electable socialist politician against Eugene Debs. Who could stand up to that? I don’t think I’ve heard Jeremy Corbyn or Kshama Sawant speak much about abolishing the wage system either. But such a comparison does hopefully cast light on why some socialists are nonplussed about Bernie Sanders. A masseur is no good when what one wants is a surgeon. Band-aids don’t fix bullet holes.

Neither Socialism Nor Barbarism: Making America Great Again (Again)

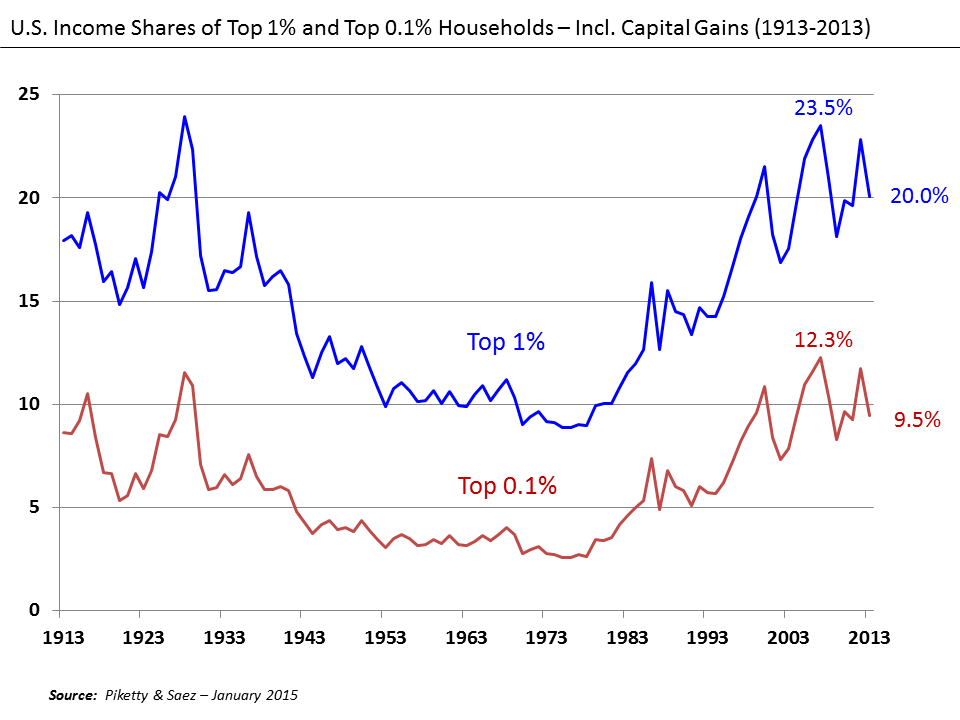

The graph below shows the share of all income which went to the richest 1% (blue) and 0.1% (red) of American families over a 100-year period from 1913 to 2013:

Note the relatively flat bit spanning about thirty years starting after World War II and continuing until around 1978 during which income inequality was at its lowest. The economist Fredrich Hayek referred to those years as the Great Prosperity. They were characterized by Keynesian-inspired welfare policies aimed at maximizing employment and a post-Fordist economy of domestic manufacturing with strong labour unions and high wages. An unprecedented number of workers (among men) made a “family” wage and could afford to buy many of the products they helped produce which spurred business and incentivized further domestic investment, jobs, and spending.

That is the America Bernie Sanders is nostalgic for. But even while the apparent health of that period (notwithstanding the millions of less-lucky American families who lived in poverty) was made possible by many concessions to the working class (Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society), those concessions comprised a temporary capitalist alternative to socialism, not its expression. It didn’t take long after the postwar world stabilized for the capitalist class to remove its restraints whenever convenient to return to a renewed, more profitable liberalism.

Obviously the current trend of high and rising inequality cannot be sustained indefinitely. If the capitalist state can’t get control of the capitalists under its charge, then everybody faces a future of economic and environmental ruin. In that sense members of the ruling class, who always have the most to lose, might be wise to feel the Bern. But it’s not clear that last century’s methods of saving capitalism would find success again.

The overall U-shape apparent in our graph above was made famous by French economist Thomas Piketty in his book Capital in the Twenty-First Century. By looking at tax records in the United States, France, Germany, and several other countries, Piketty and his team found that the low-levels of wealth inequality during the Great Prosperity was a singular occurrence, an aberration from the normal path of capitalism on which returns from capital tend to outpace income from labour. (At the bottom of the last page of the copy of Piketty’s Capital I’m consulting, a previous library patron penciled this mini-review: “577 pages to say the rich get richer & the poor get poorer.”)

Piketty, who is himself a social democrat with “no interest in denouncing inequality or capitalism per se,”[8] presents a rather dismal outlook for the future of capitalism. The best try at regaining democratic control over the globalized financial capitalism of this century, he says, would be for nation-states and financial institutions dedicated to transparency to somehow work together to approximate a global progressive tax on capital. But as one reviewer for The Guardian responded to Piketty’s proposed restrictions on capital, “It is easier to imagine capitalism collapsing than the elite consenting to them.”[9] More generally, as a Marxist critic of Piketty pointed out, “Capitalism can dispense with democracy more easily than with profits.”[10]

The democratic socialist guise of Sanders' New Deal liberalism, then, is a regressive walk back toward an antiquated capitalist society which, in the light of Piketty’s data and the global nature of modern capitalism, may no longer even be within reach.

Socialists vs Bernie Sanders and the Democratic Party

Of course American socialists don’t expect to be presented with an actual socialist who they can vote for as a viable candidate. But they do have hope that an independent social democrat is possible. Most of the criticism Sanders has received from the socialist press is directed at his strategic choices: specifically the efficacy of working with or within the Democratic Party rather than building an independent political movement to challenge the two capitalist parties.

A younger Sanders may have criticized himself on the same grounds. In his book about becoming a US Representative for Vermont he commented on the Labor Party slogan (“The bosses have two parties. We need one of our own”) with “Hard to argue with that.”[11] And here’s an excerpt from that video he wrote about Eugene Debs:

Every four years the Democratic and Republican parties come forward and tell the working people of this country all they’re going to do for them. How they’re going to end unemployment, raise wages, lower prices, and stop war. Gene Debs didn’t believe a word of it. He believed that the only way that workers could protect their own interests was to have a political party of their own: a socialist party.

Socialists who are not optimistic about expending their efforts on the electoral politics of a capitalist party see the Sanders campaign as little more than a mechanism to “sheepdog” potential leftists, attracting them to and keeping them within the Democratic Party where any potential for radical change will be dissipated or even redirected toward strengthening the established order. I don’t know who first coined the phrase, but the ability of the Democratic Party to attract and neutralize radical movements has earned it the reputation among activists as being “the graveyard of social movements.”

As the primaries began in 2016 and Sanders proved his electability by remaining neck-and-neck with Clinton in polls, the tone of the socialist press predictably became less concerned with Sanders' inevitable loss and subsequent endorsement of Clinton and more concerned with defending Sanders against Clinton and the mainstream Democratic Party. And then Trump’s surprise Republican nomination had something of a simultaneously accelerating and abortive effect on the usual dynamics between the Democratic Party and the grassroots movement it sought to absorb as both the party and its discontents turned their focus to Trump.

At the beginning of the 2020 Democratic primaries, after three years of a Trump administration, Sanders' campaign has in many ways started in arguably a stronger position among socialists than last time: more American leftists than ever are so disillusioned that they are willing to support a social democrat even as he is seeking the nomination of an unfriendly and powerful capitalist political party.

Further Reading

-

Michael Harrington died of esophageal cancer in 1989, but not before he completed his final contribution to socialist thought. Socialism: Past and Future is still readable as a clear history and explanation of socialism (from a macro-economic or political view). The hopes he expresses in Socialism for a “visionary gradualism” represent one of the most articulate cases for democratic socialism that I know of.

-

Tom Hall and Barry Grey’s “Is Bernie Sanders a socialist?” (WSWS, 16 July 2015) contrasts Sanders' politics with several principles of socialism. As a comprehensive socialist rejection of Sanders, it is the most concise that I’ve seen.

-

For something more positive about both Sanders and his choice to run as a Democrat I recommend Eric Lee’s “The Sanders Revolution” (2016)