SWAT Team Fife

In The Andy Griffith Show, the town of Mayberry has two cops: the cool, competent Sheriff Taylor who refuses to carry a gun, and the excitable, cowardly Deputy Fife who is so jumpy that he is not allowed to keep his service revolver loaded and yet still manages to prematurely fire it in stressful situations.

American policing has decidedly settled on the model of Fife — sans the precaution of keeping sidearms unloaded during non-emergencies. As yet another reminder that giving firearms to police officers does not impart to them a corresponding bravery or levelheadedness, here is a recent headline I would have missed if I were not a member of some running discussion boards:

“Woman with Airsoft Gun Delays Rock’n’Roll Marathon After Bizarre Kidnapping,” Times of San Diego (3 June 2018)

Police responded to a distraught woman in a parking garage who was holding an airsoft gun to her head. The first officer to arrive was so eager to kill the woman that he discharged his weapon early and shot himself in the leg. Another officer successfully opened fire, but missed the subject who then threw her toy gun off the parking structure and was taken into custody. (Despite the headline, other news agencies have reported that this incident was unrelated to an earlier kidnapping report.)

Unfortunately, well-armed cops literally shaking in fear as they confront with deadly force members of marginalized groups and emotionally exhausted individuals is standard operating procedure for American police. Just last week four police officers, after receiving reports that she may be suicidal, performed a “wellness” check on Chelsea Manning by breaking into her apartment with guns and a taser drawn (she was not home, but The Intercept has published a security camera video of the incident). The homicidal response of American police to any sort of emergency is so well known that it is often weaponized by petty or political enemies as another recent headline reminds us: “The home of Parkland survivor David Hogg was swatted this morning”.

Iconic, in my mind, of the sharp contrast between the armament amassed by police and their near total lack of courage and sympathy when faced with someone in need is the 2012 case of Milton Hall. Accused of stealing a cup of coffee from a Michigan gas station, Hall (a 49-year-old homeless black man) drew a small Swiss Army type pocket knife to keep the responding police officers at bay. Police immediately escalated the situation. Dash cam and witness cellphone video show that eight police officers (including a K9 unit) formed a semi-circle around Hall. Six of the officers had firearms, both handguns and rifles, trained on Hall who was squatting in a defensive position with the small knife in his hand. At one point, the K9 handler backed up and Hall seemed to relax and took a step toward the police officers. All six officers opened fire, discharging 46 rounds in a few seconds and killing Hall. (I describe the death of Milton Hall and three other homeless men murdered by police in my essay “When Police Kill the Homeless”.)

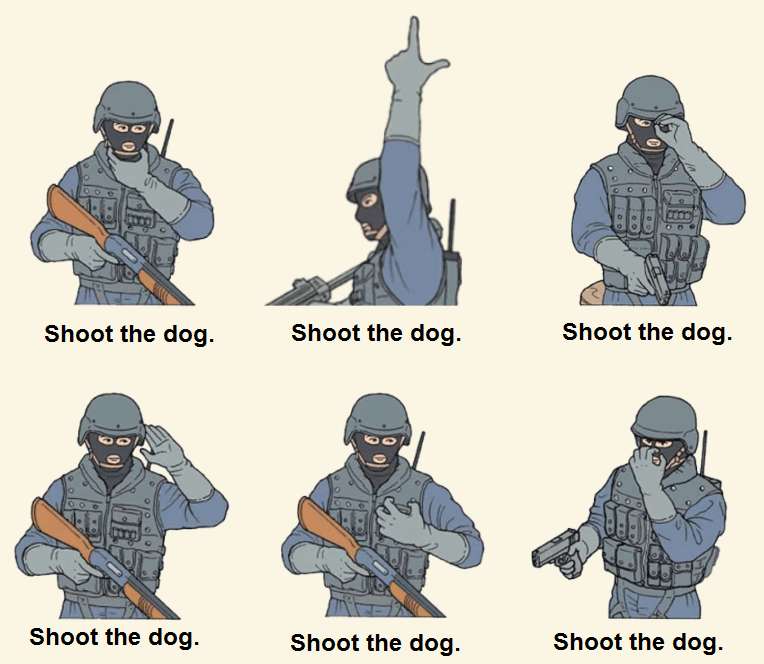

One indicator of the depth of the cowardice, barbarity, and impunity with which police kill is the shear number of family pets shot by police in America every year. Most police shootings in most departments involve dogs, but nobody keeps track of how many are killed by police nation wide. The Puppycide Database Project has collected data on over 2,900 dogs shot by police so far. In headline after headline the shootings are unprovoked, a function of police being armed, undisciplined, unaccountable, frightened, and predisposed to violence. A 2014 article titled “Can Police Stop Killing Dogs?” in POLICE magazine quotes a Department of Justice specialist, in what I hope is an overly high estimate, that as many as “25 to 30 pet dogs are killed each day by law enforcement officers.” That’s each day.

But one of the most infuriating behaviors of American police is the readiness with which so many officers arrive on a scene, heart pumping with fear, to quickly shoot an unarmed human suspect — disproportionately so if the suspect is a racial minority. In the case of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black kid who was innocuously playing with an airsoft gun at a park near his home, “quickly” meant less than two seconds after officers drove up to him. But in cases of actual danger, when people need protection from armed perpetrators, cops decked out in tactical gear too often become suddenly preoccupied with their own safety.

When I was a freshman in high school, a nearby school became the site a mass shooting. The two perpetrators planted propane bombs in the cafeteria set to detonate during lunch — when around 500 students would be in the room — and then positioned themselves in their cars with semiautomatic weapons and shotguns to shoot fleeing survivors. When the bombs failed to explode, the two improvised and became pioneers of the modern shooting rampage. According to the Columbine Review Commission report (all parenthetical page numbers refer to this document), “six officers from the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office had arrived on the scene within minutes after the attack had begun” in addition to four Denver police officers (including three SWAT team members). (38) As the killing spree continued inside the school for about 40 minutes before the shooters committed suicide, the police outside the school — with their superior and growing numbers, firepower, armor, radios, and training — did almost nothing to intervene or put themselves in danger.

At one point early in the shooting, the Denver SWAT members on scene witnessed one of the shooters stick the barrel of his gun out a door and fire several rounds. “Two of the Denver officers fired at the doorway, but it is not known why the Denver officers, who were fully equipped with high-powered weaponry and body armor, took no further action.” (33, note 80)

Even after receiving a description of the shooters, and while unarmed students and teachers did what they could to rescue each other, the armed police continued in their cowardice. “It was reported that at least one student who had managed to escape from the school (and who had carried out a fellow student with him) told the police outside the school that there were only two gunmen and urged that the police go in after them to prevent further killing. But instead of entering the school, the police first began to set up a security perimeter around the school so that the gunmen could not escape.” (60, note 152)

The worst of the carnage took place in the library about fifteen minutes into the shooting, where for almost eight minutes dispatchers knew where the killers were and police continued to safely tend to their security perimeter outside. “At that point, Patti Nielson dropped the telephone — leaving the line open — and sought refuge under a desk. Dispatchers could hear the ensuing carnage as the perpetrators in a seven-and-one-half minute killing spree taunted and executed nine more students, while sparing others.” (30)

In fact, no attempt to enter the school was made by police until 12:06pm, about the same time the shooting ended. That initial entry resulted in two staff members being escorted safely from the school. A second attempt by SWAT to enter the school, this time near the library where the perpetrators were already dead, did not go as smoothly. As officers approached the door they were spooked by a reflection of themselves in a window, which they shot before retreating (in order to “reassess the situation”). (43, note 103)

Police did not enter again until an hour after the shooting had ended. “Regrettably, wounded students remained in the library awaiting rescue during the period of time police had postponed entering the school’s west side.” (44) As victims bled to death in the school, SWAT teams moved very slowly and cautiously through the hallways. “The sheriff’s report implied that the officers faced too many unknown hazards for them to move more quickly, but in an interview with a law enforcement trade journal, Williams later stated that the officers ‘went in with superior weapons. We had HK MP5’s (automatic sub-machine guns), assault rifles, gas guns, shotguns, as well as sidearms. We entered with Army helmets with Kevlar, ballistic tactical jackets with steel plates in the front and ballistic shields.’ Despite such weaponry and armor, the record reflected that a burned carpet, spent and unlit ordnance, unfired bullets and broken glass had deterred officers from conducting a swifter search”. (53, note 132)

It took an hour and a half for police to reach the science room where students and teachers were performing first aid on victims — whom the police commenced to rough up. “Teacher Alan Cram characterized the SWAT officers as ‘very abusive;’ they would not listen to him as he tried to tell them” the whereabouts of a wounded teacher. (53) It took police over three hours after the shooting stopped to make it to the library where most of the victims were. In the Columbine episode of the television series Zero Hour, Randy Brown, the father of one of the students who knew the shooters, described the scene outside the library as he understood it:

One of the things the police don’t want you to know about that day is that on April 20th, while the executions are taking place, while these innocent children are being murdered in the library, the outside library door is propped open. And the policemen that are standing by their cars on the lawn outside are listening to these children being murdered. And they listen, and they listen, and they never rescue them. And they let them be murdered.

Yet it took less than two seconds to shoot and mortally wound Tamir Rice for playing with a toy gun.

I don’t mean to imply that cowardice or violence should be at the root of a criticism of policing in general, but the inverse relationship that seems to hold between the degree to which police are armed and the heroics of their actions is a tragic phenomenon which goes along with the transparency of American police in fulfilling their class roles.