The Loan, the Witch, and the Market: Microfinance and the re-exploitation of women

❤️

For Mindy

Preface

This booklet began as an essay about the microlending website Kiva.org and the interest rates charged to poor borrowers by its financial field partners. It has become my attempt at an introduction to Marxian economics and materialist feminism. In retrospect, the research and writing I put into this essay (over the course of several years) were mostly to the benefit of my own learning as I sought to clarify my position on various controversies. But of course I hope I’ve put down a few notes of interest to other readers as well. In particular I hope the introductory material is adequately clear so that a reader previously unfamiliar with the topics discussed will be able to go on and read the works listed in Chapter 4, Further Reading if they desire (as well as the wealth of Marxist and feminist material available elsewhere).

Due to the personal nature of my methodology, the selection of sources throughout the essay follow somewhat haphazardly the whims of my curiosity rather than a systematic exploration of the issues. Although this has resulted in an essay which is clearly polemic in nature, I’ve tried to engage and synthesize most major positions and relevant academic treatments. Unfortunately, in an attempt to keep things concise, my impressionable voice may have adopted something of a pseudo-scholarly and arcane tone in mimicry of my academic sources. For that reason I feel I should state my main thesis in plain language at least once from the outset, and that is that most of the billions of people in the world today already do too much work, particularly women, especially in the so-called third-world or developing countries, and any scheme which promises to improve life by giving poor women more work to do ought to be met and examined with the utmost suspicion.

The good news is that nobody needs to read this entire essay. Each top-level section should be mostly standalone and readable on its own.

Readers only interested in Kiva should instead read my shorter essay “Some thoughts on Kiva’s interest rates”

Readers only interested in an introduction to neoliberalism and Marxian economics should read Chapter 1, Capitalism but skip the lengthy Chapter 2, Housework. Anyone interested in the debate over socialist markets may also want to read much of Chapter 3, Alternatives.

Readers only interested in an introduction to materialist feminism should read all of Chapter 1, Capitalism or at least Chapter 2, Housework.

Acknowledgements

This essay is less bad than it could have been thanks to Louis Burkhardt, Evan Apel, and Nate Pierce who were kind enough to read early versions of this essay and provide valuable suggestions and corrections.

The canonical version of this essay can be found at https://americancynic.net/log/2018/12/3/kivas_interest_rates/

1. Capitalism

1.1. Microfinance as neoliberal financialization

Contemporary capitalism is financialized capitalism, and microfinance is its response to poverty.[1]

The Political Economy of Microfinance

Microloans are small, short-term lines of credit given to entrepreneurs who lack access to more traditional financial services. The goal is to improve the quality of life in developing and conflict-torn regions where it is hoped that borrowers can make effective use of even very small, expensive loans. The efficacy of microfinance at alleviating poverty has been a matter of research and debate since Muhammad Yunus founded the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1983 (Yunus and the Grameen bank were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006). The early anecdotal reports of success and the prospect of a business-friendly cure to poverty created an increasing excitement around microfinance for over two decades. But in recent years expectations have sobered.

Most Americans who are familiar with microfinance were likely introduced to it through Kiva Microfunds, a nonprofit organization whose website allows users to provide money toward filling small personal and business loans to individual borrowers around the world. The loans are disbursed by Kiva’s field partners called microfinance institutions (MFIs). Despite its founders' original intention of allowing users to realize gainful returns on their loans, nether Kiva itself nor its users/lenders collect interest on loans which has contributed to the impression that microfinance is a purely philanthropic project.[2]

But some MFIs have shown themselves to be nothing more than predatory banks, as typified by the 2007 IPO of Compartamos Banco in Mexico which raised millions of dollars of equity for investors with its business model based on charging groups of women very high interest on microloans.

In October 2010 the microfinance industry in the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh self-destructed in a frenzied lending bubble accompanied by aggressive collection practices.[3] Hundreds of suicides in the region have been linked to microfinance debt and harassment at the hands of loan agents. The Associated Press reported the following details about some of the suicides linked to an MFI called SKS:

One woman drank pesticide and died a day after an SKS loan agent told her to prostitute her daughters to pay off her debt. She had been given 150,000 rupees ($3,000) in loans but only made 600 rupees ($12) a week.

Another SKS debt collector told a delinquent borrower to drown herself in a pond if she wanted her loan waived. The next day, she did. She left behind four children.

One agent blocked a woman from bringing her young son, weak with diarrhea, to the hospital, demanding payment first. Other borrowers, who could not get any new loans until she paid, told her that if she wanted to die, they would bring her pesticide. An SKS staff member was there when she drank the poison. She survived.

An 18-year-old girl, pressured until she handed over 150 rupees ($3)--meant for a school examination fee—also drank pesticide. She left a suicide note: “Work hard and earn money. Do not take loans.”

In all these cases, the report commissioned by SKS concluded that the company’s staff was either directly or indirectly responsible.[4]

A 2012 paper by outspoken microfinance critic Milford Bateman (author of Why Doesn’t Microfinance Work?: The Destructive Rise of Local Neoliberalism) and influential heterodox Cambridge economist Ha-Joon Chang described the microfinance model as “most likely” a “poverty trap” at the individual and community level, and as a mis-allocation of capital at the national level.[5]

In the past five years or so several rigorous studies which use a randomized method to compare the effects of microfinance on borrowers have appeared in the academic literature. The result of one recent survey of six such studies found that “The studies do not find clear evidence, or even much in the way of suggestive evidence, of reductions in poverty or substantial improvements in living standards. Nor is there robust evidence of improvements in social indicators.” But the same survey also found “little evidence of harmful effects, even with individual lending […] and even at a high real interest rate.”[6]

An infographic published by Kiva in celebration of its 10th year of operation draws attention to the fact that 75% of borrowers have been women and that nearly 400,000 farmers in the least developed countries have received loans made possible by Kiva.[7] Both of these groups — women and subsistence farmers — are specifically targeted by Kiva through programs like the dollar-matching Women’s Entrepreneurship Fund (a partnership between Kiva, the US State Department, and the Inter-American Development Bank) and Kiva’s “Financing Agriculture” lab which hopes to use microloans to alleviate the cycles of risk inherent to small-scale farming.

The gender composition of Kiva lenders (users of Kiva.org) skews in the same direction as that of its borrowers: about 67% are women. Most lenders are in wealthy countries: by dollar amount, over 70% of loans are lent by users in the United States, Western Europe, and Canada.[8] In addition to individual users, Kiva collects donations from institutional partners and corporate sponsors. Among Kiva’s corporate sponsors who have given $1 million or more during the past 30 months, most of them are financial institutions (including Capital One, Deutsche Bank, and Moody’s). Among the others are foundations associated with large, multinational corporations (including HP, PepsiCo, and Google).[9]

On one hand these demographic and geographic distributions, wherein sympathetic people in parts of the world with extra money are providing charitable loans to people in parts of the world with not enough money, are not surprising. Those are exactly the sort of relationships Kiva exists to facilitate per its mission statement, after all. But Kiva’s entire model of microfinance takes for granted that there are a great number of women and peasants at the developed world’s periphery who are in desperate need of financial services without attempting to explain why the world’s wealth has become so stratified by lines of geography and gender, and without any introspection into its own role in the greater processes of global capitalism arising from and transforming those lines.

Most academic criticism of microfinance investigates its role as a neoliberal institution. A vague and contentious term, but used too heavily within academic theory to avoid, neoliberalism is so-called because it represents an attempt to return to or rescue the ‘free-market’ optimism of classical liberalism from the Keynesian and social democratic trends of the twentieth century. It generally refers to the economic policies that became dominant at the end of the 1970s which seek market creation and uninhibited international trade, financialization (seeking profit in financial markets rather than directly investing in production), and financial imperialism (including the practice of providing credit in exchange for political influence and the imposition of austerity measures in debtor countries).

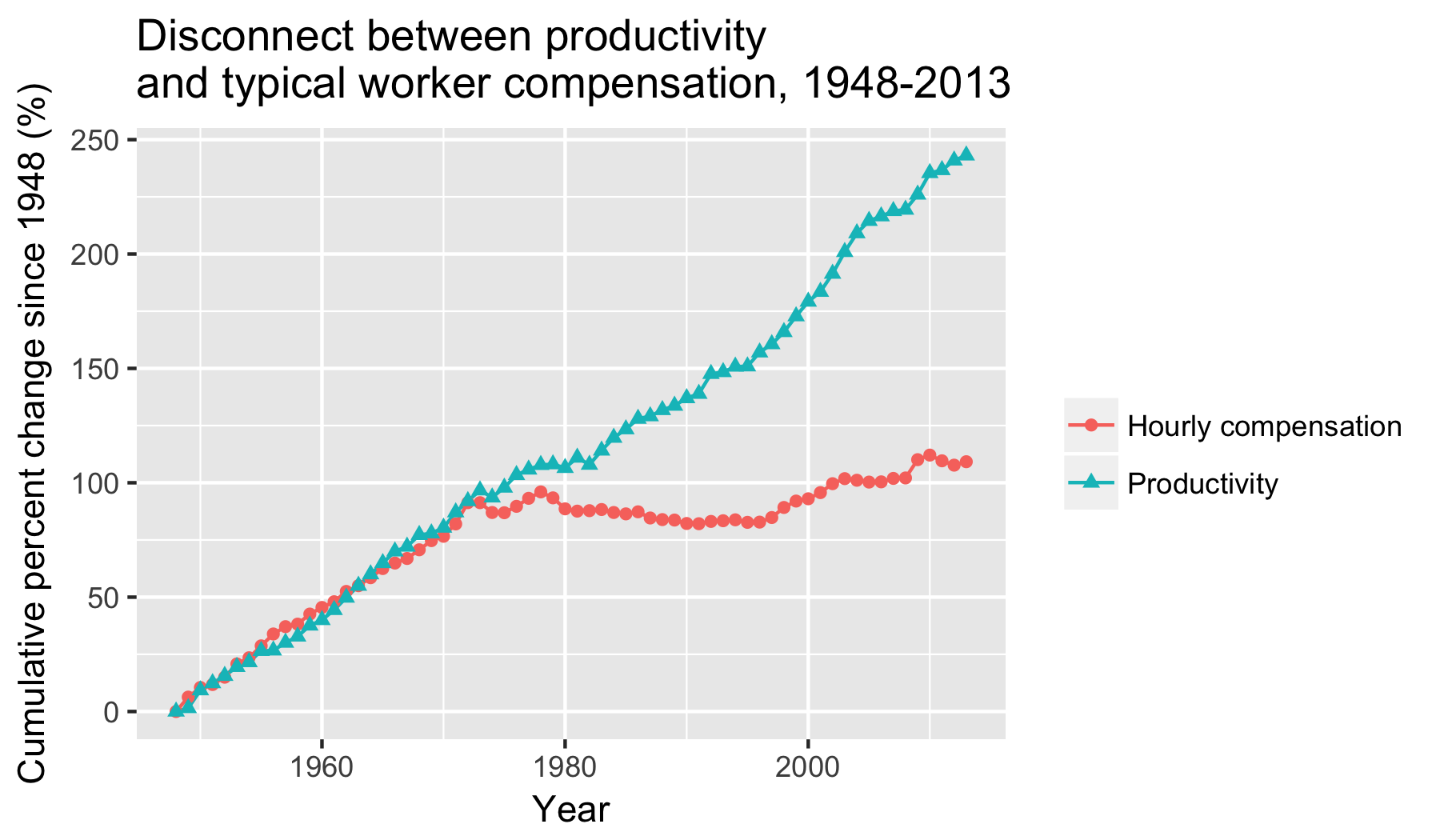

In his postface to The Road from Mont Pelerin (a collection of essays exploring the intellectual origins and development of neoliberalism), Philip Mirowski provides eleven defining traits which together give a description of the neoliberal project “as an authoritarian variant of the liberal tradition,” wanting a strong state, sufficiently insulated from democracy, to create and maintain its markets.[10] The successful effects of neoliberal policy in the United States are strikingly illustrated by plotting the change in real hourly wages on top of the changes to net domestic product as in the figure below: since the mid 1970s wealth from increased productivity is going almost entirely to owners rather than to the wage-earners doing the work. (Similar illustrations of the neoliberal break can be seen by examining plots of wealth and income share for the same time period.)

The academic perspective of microfinance as a neoliberal tool considers it as a method by which capital can gain access to and exploit the peripheral poor who were previously outside of the core economic sphere.[12] Microfinance, then, plays a similar role at the frontiers of capitalism as subprime lending plays within the borders of financial centers. As the geographer Katharine Rankin has noted, in the wake of the 2007 financial crisis two seemingly contradictory attitudes toward the populations targeted by these two forms of “poverty finance” emerged. The recipients of subprime loans (variable-rate mortgages and expensive credit cards), mostly racialized minorities in American cities, were “disparaged as irresponsible, risk-embedded subjects,” while the recipients of microcredit, mostly third-world agrarian women, were still “enrolled as responsible, risk-averting subjects” into profitable microfinance schemes.[13]

Despite such different initial reactions, Rankin concludes from the parallel trajectories of both groups that “there is every reason to expect that the latest frontier of speculative arbitrage will expose a widening set of households, neighbourhoods and regions in the Third World to financial shock and to material and socio-emotional forms of dispossession.”[14] It would seem that the 2008 crises in Nicaragua (Section 3.3, “Debt strike”) and the disastrous 2010 collapse in Andhra Pradesh can be seen as waves of the shock reaching the microfinance sector.

Rankin gives a description of neoliberalized microfinance as a tool of capital expansion that “is dispossessive to the extent that it extracts wealth not through primary exploitation in the realm of production or the direct enclosures of primitive accumulation, but through predation and fraud that turns poor households into new markets for financial instruments.”[15] Rankin’s Marxian terminology brings together several important concepts upon which we can conveniently expand.

1.2. “Primary exploitation” (wage labour and accumulation)

In the context of macro-economics, exploitation refers to the process by which a portion of the surplus produced by a society is taken and used for the benefit of a parasitic group, either a foreign conqueror or an endemic owning class. Each such class society can be characterized by its primary means of exploitation. While history provides a handy menu of legal schemes for implementing exploitative systems (tribute, tax, rent, usury, profit), the primary means of exploitation is determined by the prevailing organization of productive forces. In slave societies, for example, exploitation is naked and workers are often coerced with open force: slaves are made to produce enough to maintain their own meager existence, and then forced to continue to work to maintain much of the rest of society’s needs. In the various serf and sharecropper arrangements, peasants and bonded farmers are allowed to support themselves, but a portion of their harvest is taken by landlords to support the other classes.

In capitalism, exploitation is carried out primarily through a more subtle system of wage labour: when the value created by workers is more than the value of the wages they receive, the difference (what Marx called “surplus-value”) is kept and controlled by business owners and executives. A portion of the surplus-value is consumed by the owning classes (sometimes at lavish levels), but in large projects the majority of surplus-value becomes profit and is re-invested as capital where it can be used to extract even more surplus-value from workers to be re-invested, and so forth. This ‘self-expanding’ process by which capital exploits wage workers to become ever more capital is called the “accumulation of capital.”[16]

1.3. “Primitive accumulation” (dispossession)

The simplified description of capital accumulation presented above is of a self-contained process which presupposes the existence of capital but doesn’t explain how it got started in the first place. In an allusion to a phrase used by Adam Smith, Marx referred to the basis of capitalism, the initial concentration of property and creation of propertyless workers, as “so-called primitive accumulation” which “is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production.”[17] “Primitive accumulation” is a rather unfortunate but standard English translation of ursprünglich Akkumulation, “original accumulation.”

But as Marx pointed out, the peaceful account of primitive accumulation consisting of frugal industrialists employing liberated peasants told by the bourgeois economists of his time (and ours) is only half of the history. The other half — the story of how peasants are brutally forced off of the lands and out of the homes which provide their sustenance, how skilled artisans are alternately displaced by machines and then used as machines — in short the story of how a sufficient workforce for a nascent capitalism can be assembled by so thoroughly stripping individuals of their possessions and their relationships on such a wide scale that it becomes possible to hound them into factories, mines, and farms to work for wages — is left untold. “And this history, the history of their expropriation, is written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire.”[18]

1.4. The two-stroke engine of accumulation

To recapitulate: the basic everyday mechanism of capitalist accumulation is wage work which is experienced by most people in capitalist society as the normal workday, by the paycheck stub and the loan statement (or by the stress of unemployment and the loan statement). Normal accumulation is the extraction of profit from those people already integrated into the capitalist system. Primitive accumulation, on the other hand, is direct dispossession, usually carried out by state-sponsored violence. Examples of primitive accumulation which are happening somewhere today include peasants and indigenous peoples being forced off of their lands, foreclosures on homes, and asset forfeiture processes (like those enforced as part of America’s racialized “war on drugs”). Primitive accumulation directly extracts wealth through the theft of resources, but more importantly it produces propertyless people who can then be integrated (or further integrated) into the capitalist system of wage work (or prison slave work), or into the debt-bound ranks of the wage-suppressing unemployed.

Some Marxist descriptions of capitalism treat primitive accumulation as a historical process which got capitalism started in a given region but which no longer plays a role in its reproduction. Such views reflect the fact that in Capital Marx was mostly concerned with critiquing capitalist production on its own terms. Toward that end he theorized the employee-employer relationship itself as a market transaction where the employees' ability to do work is sold to employers as a commodity called ‘labour-power.’ From that distinguishing transaction, where the worker’s labour-power becomes the unique commodity that can produce more value than it costs, he demonstrated how capitalist exploitation and accumulation takes place even in an ideal (fair and free) market where “all commodities, including labour-power, are bought and sold at their full value”[19] In such an idealized pre-existing market, profit is extracted and re-invested through the normal mechanism of waged exploitation, without the need for further dispossession. Correspondingly, Marx’s description of primitive accumulation is largely relegated to the short eighth (and last) part of the first volume of Capital (where it deals mainly with England and English enclosures as representative of the “classic” process by which capitalism emerged out of feudalism in Western Europe).

However, trying to describe capitalism without acknowledging the role of ongoing primitive accumulation is like trying to describe the action of a two-stroke engine based on its driven downstroke alone while only vaguely acknowledging that the upstroke, which brings fresh fuel into the cylinder to be compressed, must have occurred some time in the past. In fact the upstroke is not only the prerequisite of the downstroke, it is also its consequent. The piston’s own momentum, constrained by the geometry of its linkage to the crankshaft, carries it back up on every cycle causing both strokes to repeat until the supply of fuel is exhausted or a catastrophic mechanical failure occurs.[20]

The process of capitalist accumulation and expansion, carried on according to its own momentum and constraints, similarly consists of two self-propagating steps:

-

Dispossession

-

Integration & [re-]exploitation

1.5. Crises and fixes

The two-stroke engine of accumulation works so well that it periodically suffers from so-called crises of overaccumulation, a victim of its own success. When the extraction of surplus-value outpaces the demand for the resulting capital, investors have trouble finding profitable investments and existing productive assets lose their value. Likewise, when production of consumer goods outpaces demand, markets become flooded with products which nobody wants or can afford to buy. When investments in technology lead to increased automation at a rate which outpaces growth, the result is more layoffs than new jobs which further exacerbates the problem of overproduction (as unemployed people can afford even fewer commodities).

Taken together, capitalist crises — and the history of capitalism as recorded in the headlines of the popular press is a series of booms followed by gluts, recessions, mass layoffs, market crashes, and depressions — are characterized by investors who have money they can’t profitably invest, unemployed workers who can’t find work at a wage to live on, and markets full of abundant goods which people don’t need or which needy people can’t afford.

In The New Imperialism David Harvey describes two methods or “fixes” to which investors and policymakers can turn in order to temporarily stave off the effects of overaccumulation. A “temporal fix” seeks to maintain profit rates by investing excess capital into long-term (and large scale) projects such as expenditures on social services, education, research & development, and infrastructure. A “spatial fix” seeks a renewed rate of profit by extending geographically: investing in developing parts of the world and gaining access to new markets and pools of cheap workers in parts of the world where people are not already fully integrated into the labour market — often by displacing subsistence farmers and finding ways to extract more surplus-value from the self- or pseudo-employed participants in the informal economies of developing regions.[21]

These spatio-temporal fixes, as Harvey calls them, can be roughly mapped to the two-steps of capitalist accumulation: spatial fixes, by which capitalism extends itself geographically, depend on the availability of a dispossessed workforce to be employed by exported capital and correspond to the first step (“dispossession”); temporal fixes, which are merely instances of usual capitalist exploitation and re-investment intensified in time, correspond to the second step (“exploitation”). Taken together, spatio-temporal fixes allow capitalism to expand through what Harvey calls “accumulation by dispossession,” a term chosen to emphasize the ongoing nature of what Marx called primitive accumulation expanded to include:

“the commodification and privatization of land and the forceful expulsion of peasant populations […]; conversion of various forms of property rights (common, collective, state, etc.) into exclusive private property rights (most spectacularly represented by China); suppression of rights to the commons; commodification of labour power and the suppression of alternative (indigenous) forms of production and consumption; colonial, neocolonial, and imperial processes of appropriation of assets (including natural resources); monetization of exchange and taxation, particularly of land; the slave trade (which continues particularly in the sex industry); and usury, the national debt and, most devastating of all, the use of the credit system as a radical means of accumulation by dispossession. The state, with its monopoly of violence and definitions of legality, plays a crucial role in both backing and promoting these processes.”[22]

Such a mapping emphasizes an extensive (spatial fixes, dispossession) and intensive (temporal fixes, regular capitalist exploitation) interpretation of the two steps of accumulation which, taken in combination, give rise to the neoliberal forms of primitive accumulation noted by Harvey. Another extensive-intensive pair which can similarly be analyzed in terms of capitalist accumulation is that of globalism and nationalism: the play of transnational corporations, banks, and governing bodies with that of the chauvinism of nation-states. These dynamics define capitalism’s shape at the global scale: imperialism.

1.6. Imperialism and war

Marx died in 1883, decades before the Great War of the twentieth century, but he was aware that capitalism’s origin in slavery and colonialism meant a future in world war:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the indigenous population of that continent, the beginnings of the conquest and plunder of India, and the conversion of Africa into a preserve for the commercial hunting of blackskins, are all things which characterize the dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief moments of primitive accumulation. Hard on their heels follows the commercial war of the European nations, which has the globe as its battlefield.[23]

The first great period of capitalist imperialism, during which the industrial powers extended and divvied up their colonial holdings according to their respective military power, emerged at the end of the Nineteenth century and eventually led to the world wars of the twentieth century. In his influential booklet which summarized several characteristics of the capitalist imperialism of that time, Lenin noted the increasing role of financialization in international relations — “The world has become divided into a handful of usurer states and a vast majority of debtor states” — a trend which was resumed in the 1970s as a characteristic feature of neoliberalism after capital accumulation outgrew the “fixes” provided by the wars and the postwar New Deal.

Lenin called his book Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, but for Hannah Arendt “Imperialism must be considered the first stage in political rule of the bourgeoisie rather than the last stage of capitalism.”[24] Unlike classical Marxism, Arendt was not preoccupied with the internal economic laws of capitalism and considered openly-violent primitive accumulation, not the peaceful appearance of wage labour, to be the true ideal toward which capitalism had always striven and which was fulfilled in imperialism:

The bourgeoisie’s empty desire to have money beget money as men beget men had remained an ugly dream so long as money had to go the long way of investment in production; not money had begotten money, but men had made things and money. The secret of the new happy fulfillment was precisely that economic laws no longer stood in the way of the greed of the owning classes. Money could finally beget money because power, with complete disregard for all laws — economic as well as ethical — could appropriate wealth. Only when exported money succeeded in stimulating the export of power could it accomplish its owners' designs. Only the unlimited accumulation of power could bring about the unlimited accumulation of capital.[25]

Imperialist adventures allowed capital to escape its cloak of “voluntary” wage work and economic neutrality, at least in the distant lands it conquered, and step to its place as a more effective if naked system of exploitation. Investing in war machines to protect international business concerns (and to pulverize fixed capital in faraway places, which can then be profitably re-built at government-contractor rates) is simultaneously a temporal and spatial fix, hence the continued importance of the military-industrial complex in sustaining capitalist profit.

“Globalization” (or “globalism”) when used in a positive connotation today is usually a euphemism for neoliberal imperialism which carries with it optimistic visions of lasting trade-facilitated peace among nations, enough credit to smooth over crises, and the cosmopolitan freedom to transcend borders. Similar hopes were attached to the imperialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before they disappeared in depression, world wars, and holocaust. Capitalist globalization does not harmonize national interests; it harnesses them for the cause of war. As Arendt noted in her description of imperialism (as a preparatory step toward fascist totalitarianism), “In theory, there is an abyss between nationalism and imperialism; in practice, it can and has been bridged by tribal nationalism and outright racism.”[26]

The US invasion of Iraq during the Persian Gulf War of 1990-1991 shattered any lingering hopes that the neoliberal version of imperialism could be conducted without the use of direct military force (or at least of ground troops). But of course war and financialization are not at odds with each other — they complement each other, and usurer states pursue their interests with both tools.[27]

While coalition forces were bombarding military and civilian infrastructure in Iraq, negotiations were already underway between Canada, the United States, and Mexico regarding the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), an iconic piece of globalist legislation drafted under the first Bush administration and signed into US law at the beginning of the Clinton administration. As part of its preparations for joining NAFTA, the Mexican government implemented a series of neoliberal reforms including the abolition of protections against the privatization of communal land resulting in the removal of campesinos from their land and into wage work — a clear example of ongoing primitive accumulation.

The day NAFTA went into effect on January 1, 1994, a leftist revolutionary group in Chiapas, Mexico, the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, rose up in open insurrection against the government. Over two decades later the Zapatistas still maintain autonomous communities in Chiapas which exist in resistance to the Mexican state and perhaps more emphatically to the incursions of neoliberal globalization. Subcomandante Marcos, the now-retired spokespersona for the Zapatista movement, has described the neoliberal policies of globalization as the Fourth World War (succeeding the Cold War), “a new war for the conquest of territory.” But, he continues, “while neoliberalism is pursuing its war, groups of protesters, kernels of rebels, are forming throughout the planet. The empire of financiers with full pockets confronts the rebellion of pockets of resistance”:

Neoliberalism attempts to subjugate millions of beings, and seeks to rid itself of all those who have no place in its new ordering of the world. But these “disposable” people are in revolt. Women, children, old people, young people, indigenous peoples, ecological militants, homosexuals, lesbians, HIV activists, workers, and all those who upset the ordered progress of the new world system and who organise and are in struggle. Resistance is being woven by those who are excluded from “modernity”.[28]

Much of the subsequent grassroots opposition to neoliberalism during the 1990s was also from the left. In 1999 during a meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle, anti-globalization protesters — environmentalists, anarchists, and labour union members — dramatically overwhelmed police to shut down the meeting and helped to make “WTO” and “globalization” household words in America.

Some of the rhetoric in Subcomandante Marcos’s essay on the Fourth World War (and elsewhere) including his romantic view of culture and national identity, his bemoaning of the European Union as the ruin of European civilization, his warnings about the globalist “new world order,” and his resentment of modernity is almost indistinguishable from the anti-globalization talking points of right-wing populism. But leftists, as champions of internationalism, are not literally against globalization in the etymological sense of the word. For that reason many activists prefer labels like “alter-globalization” to “anti-globalization.” This distinction has become very important now that right-wing and nationalist movements often predominate the anti-globalization discourse.

Everywhere, but especially in countries being plundered by neoliberal policy, not only are racial and gender hierarchies being reformed to better serve capitalism, but oppressed groups continue to fight for their own liberation. The result is the loss of old local and familial forms of privilege, wealth, and exploitation at both ends — whisked out to financial centers or destroyed by feminists and other progressive reformers. In many of these places the right-wing resistance to globalization — including Islamacist militants, populist demagogues, and a resurgence of various decentralized fascist and far-right revolutionary groups — have displaced leftist movements as the dominant forces challenging the global expansion of capitalism. As one essayist has pointed out, it is an unfortunate fact that today the world’s most successful “anti-imperialists” are “a motley assortment of authoritarian regimes, right-wing populists, local capitalists trying to negotiate a piece of the action, religious fundamentalists, warlords and gangsters.”[29]

This resentful patriarchal revolt against globalism and social progress has been slowly building even in Western countries. David Harvey’s description of the nationalist backlash to neoliberalism in America during the 80s and 90s illustrates how the nationalist phenomena that consolidated around President Trump has been forming for decades:

Many elements in the middle classes took to the defence of territory, nation, and tradition as a way to arm themselves against a predatory neoliberal capitalism. They sought to mobilize the territorial logic of power to shield them from the effects of predatory capital. The racism and nationalism that had once bound nation-state and empire together re-emerged at the petty bourgeois and working-class level as a weapon to organize against the cosmopolitanism of finance capital. Since blaming the problems on immigrants was a convenient diversion for elite interests, exclusionary politics based on race, ethnicity, and religion flourished, particularly in Europe where neo-fascist movements began to garner considerable popular support. […] The prevailing mood of ‘helplessness and anxiety’ was conducive to ‘the rise of a new brand of populist politician’ and this could ‘easily turn into revolt’.[30]

Now, nearly twenty-five years after NAFTA and the Zapatista uprising, eighteen years after the Battle in Seattle, fifteen years after the 9/11 terror attacks carried out by anti-Western Islamicists and the invasion of Afghanistan by the United States (a war which has been waged for over 16 years, twice as long as the Vietnam War), thirteen years after the catastrophic second invasion of Iraq by the United States, and ten years after the 2007 financial crises, the racist and nationalist reactions noted by Harvey have re-emerged more clearly than ever. The 2016 Brexit referendum in the UK and the election of Trump in the US signal the arrival to the Anglosphere of a forceful right-wing populism driven by a patriarchal reaction against globalization.

Another important distinction, which has been made by J. Sakai, is to clarify that this anti-imperialist brand of fascism “is anti-bourgeois but not anti-capitalist.”[31] While fascists can (and often do) adopt the language, analysis, and tactics of the left,[32] they can only apply them in a superficial manner to the distant elites and liberal billionaires who encroach on what fascists perceive as their rightful means of exploitation. The old shallow trope of the good, productive industrial capitalist versus the evil, parasitic financial or merchant capitalist is the extent of the fascist critique of capitalism. Even with slogans couched in anti-capitalist or pro-worker rhetoric most fascists can’t bring themselves to offer an actual economic critique but instead malign the global bourgeoisie in terms of an imagined Jewish conspiracy. Because if fascists were to critique the engine of capitalism itself they would be undermining the very system of exploitation they hope to command.

One way imperialism is bridged to and feeds off of nationalism can be seen at work in the Trump administration which rode to power by fomenting nationalist and racist sentiment and soon shifted toward militarism and likely increased conflict (or outright war) with rival imperialists. Immediately after Trump’s election, the Democratic Party (representing the only viable political opposition to Trump) began a concerted campaign of anti-Russian propaganda using almost every media outlet available in the country. As usual, even during times of potentially great political upheaval, on the issue of imperialism and war the liberal parties are united.

1.7. Migrant work

Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus the creation of the physical conditions of exchange — of the means of communication and transport — the annihilation of space by time — becomes an extraordinary necessity for it.

Grundrisse

Owing to the combined efforts of ongoing primitive accumulation and war, one of the chief products of global capitalist accumulation is displaced people. The number of international migrants was estimated to be 258 million people in 2017 (up from 173 million in 2000), over 10% of whom are refugees or asylum seekers.[33] As climate change threatens to exacerbate wars and famines, the near future may dwarf the already unprecedented number of refugees seeking temporary shelter and new homes today.

The Syrian Civil War is currently the most active proxy theatre for the conflict between the United States and Russia (as rival imperialists), but it is also the center of the global conflict between extreme right-wing anti-globalization militants like ISIS and socialist revolutionaries defending Rojava. (This situation is reminiscent in many ways of the Spanish Civil War, a proxy war between the USSR and Nazi Germany and also between Spanish fascists and the socialist revolutionaries in Catalonia.) Since 2011, over 6 million people have fled Syria as refugees, and another 6 million are displaced (many living in camps) within its borders.[34]

In terms of scale, nothing in human history compares to the mass migration of peasants triggered by the ongoing industrialization and urbanization of China. The liberalization of China’s economy under Deng Xiaoping occurred contemporaneously with the rise of Western neoliberalism with similar aims and effects. A 2016 survey by China’s National Bureau of Statistics puts the number of long-distance migrant workers, typically rural villagers looking for jobs in cities, at over 168 million (about 45% of whom have migrated to a new province).[35] A recent report indicates that the national government’s urbanization plan includes the relocation, forced if necessary, of a further 250 million rural residents to cities by 2025.[36]

The neoliberal and NAFTA-related reforms in Mexico not only allowed traditionally communal plots of land (ejidos) to be privatized, but they also flooded the Mexican markets with subsidized corn and pork from the United States. The result was the demise of much of the country’s small-scale farm industry sending millions of rural Mexicans north to find work in the sprawling maquiladora factories near the border or to seek agricultural and domestic work in the United States. Between 1990 and 2007 (net migration has stabilized near zero following the recession) a net total of more than 8 million Mexicans migrated to the United States (almost 75% crossing the border without authorization).[37] Between 1998 and 2013 a total of 6,029 deceased migrants were found near the Mexican border by the United States Border Patrol (with close to 300 bodies being found per year since the year 2000). The actual number of migrants who die crossing the US-Mexico border is likely much higher, as the Border Patrol does not count deaths that occur on the Mexican side of the border, nor do the numbers reflect remains which go undiscovered in the desert.[38]

The Arizona-based humanitarian group called No More Deaths, which works to raise awareness of the dangers faced by migrants as well as to provide direct aid to migrants and document abuses by law enforcement, has identified several practices of the Border Patrol (whose official motto is “Honor First”) which “further increase the risk of death in the desert.” Those practices include: intentionally funneling migrants to deadly regions, impeding volunteer search and rescue operations, and vandalizing food and water drops left on migrant trails. No More Deaths has also documented abuse of migrants in Border Patrol custody, concluding in a report based on thousands of interviews with detainees, “It is clear that instances of mistreatment and abuse in Border Patrol custody are not aberrational. Rather, they reflect common practice for an agency that is part of the largest federal law enforcement body in the country. Many of them plainly meet the definition of torture under international law.”[39]

Two reports based on Freedom of Information Act requests were published in 2018 which corroborate much of the No More Deaths interviews alleging widespread abuse of detainees held by the Obama-era Department of Homeland Security agencies (Customs and Border Protection (CBP) & Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)). One report on mistreatment faced by unaccompanied minor migrants based on thousands of pages of reports obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union from the Department of Homeland Security Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties (CRCL) found that “CBP officials regularly use force on children when such force is not objectively reasonable or necessary,” including the unnecessary use of Tasers as well as verbal abuse including death threats. The report concludes that “The abuse is not limited to one state, sector, station, or group of officials— rather, the CRCL documents reflect misconduct throughout the southwest, from California to Texas, at ports of entry and in the interior of the United States, by CBP and by Border Patrol.”[40]

The second report, by The Intercept, examined 1,224 complaints of sexual abuse filed between 2010 and September 2017 by detainees in ICE custody which “suggest that sexual assault and harassment in immigration detention are not only widespread but systemic, and enabled by an agency that regularly fails to hold itself accountable.” In over 70 percent of the complaints, an officer was alleged to be the perpetrator and/or a witness. The Department of Homeland Security was only able to provide documentation of 43 investigations (an investigation rate of less than 4 percent).[41] I have found no reports of Homeland Security officials who have been indicted for crimes committed against children or other detainees in their care, but several volunteers with No More Deaths have been arrested and charged with federal crimes related to providing food, water, and shelter to undocumented immigrants.[42]

The Trump administration seems intent on continuing the inhumane immigration enforcement against refugees and other migrants at the southern border. Shortly after Trump took office, ICE and federal prosecutors began bringing more criminal charges against parents who entered the country without authorization, resulting in hundreds of children being taken into state custody.[43] In April 2018, Attorney General Jeff Sessions ordered ICE to implement a “zero tolerance” policy, institutionalizing the revanchist family separation policy — reportedly architected by senior Trump policy advisor Stephen Miller[44] — as a means to punish and dissuade migrant families (including asylum seekers). Within months, reports and photographs of the thousands of children separated from their families and herded into chain-link cages in internment camps mobilized a broad-based protest movement nationally and internationally, with some protesters utilizing occupy-style tactics to blockade ICE offices in several major American cities. Because of the public outrage, Trump was forced to sign an executive order that requires “detaining alien families together where appropriate and consistent with law and available resources.”[45]

The maquiladora system in Mexico consists of over 5,000 factories owned by multinational corporations in special economic zones (mostly near the United States border) where raw materials are imported duty-free (often from the United States), processed by nearly two million Mexican workers (historically, mostly young women) earning low wages (easily a tenth of the cost of American workers) in stressful and dangerous working conditions. The finished products are exported under reduced tariffs back to the United States.[46]

In short, the maquiladoras are desert sites of industrial wage slavery which hold millions of Mexican families in poverty, daily grinding them in production lines to extract another ten hours of their lives to be packaged up and shipped as profits back to wealthy shareholders in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The entire system, from the primitive accumulation of indigenous farmlands to the exploitation of urban labour in the factories, provides several convenient fixes for the overaccumulation of American capital:

-

the export of excess agricultural goods and raw industrial products to Mexican markets

-

the export of excess capital as investments in maquiladora plants

-

the import of wage-suppressing and easily exploitable labour to the American workforce

-

the import of cheap finished products for American consumers

A secondary benefit to the United States' capitalist class is achieved through what No More Deaths calls dispossession through deportation: migrants who are captured by U.S. border enforcement agents often have their belongings (including money) confiscated (in 5% of observed cases via direct theft by individual agents) before they are deported. This is not only a source of direct accumulation (“When Department of Homeland Security protocols are followed, much of the money goes to a CBP suspense account then eventually ends up in the U.S. Treasury fund. Many others also siphon money along the way including MoneyGram, prison profiteers such as prepaid debit card companies like NUMI Financial, and individual agents, as illustrated by cases of direct theft”), but more significantly works as an engine of primitive accumulation producing an ever more propertyless and desperate population vulnerable to a predatory economic system.[47]

It is worth noting that for decades nativists and wage-jealous white workers in the United States have loudly complained about the porous southern border, but their concerns were rarely reflected in policy which instead maintained whatever level of control at the border was deemed necessary to steer wages and keep illegal immigrants simultaneously abundant and vulnerable for the benefit of employers. It was not until recent years, when net migration from Mexico has been zero or negative, conditions which make controlling unauthorized immigration much less important to economic interests, that the strict anti-immigrant proponents (as typified by the Trump presidency) have gained influence. This dynamic demonstrates that, in the United States, racism remains subservient to and must wait its turn behind the needs of capital.

Unlike what its apologists claim, neoliberal globalization does not provide greater freedom to travel for most people. “This is a travesty of globalization — a world without borders to everything and everyone except for working people.”[48] Capital is free to cross borders in search of cheaper labour to exploit, but people are stopped, questioned, searched, detained, interned, enslaved, turned back, smuggled, drowned, lost, starved, shot, hunted down, rounded up, deported, “and to crown all, mocked, ridiculed, derided, outraged, dishonored.”

As the rise of microcredit at the periphery was mirrored by aggressive subprime lending in the urban centers, so is migration in the periphery mirrored by thousands of homeless people living in the urban centers of capitalism. The refugee camp at the border has a counterpart in the homeless camp in the city park. One study in the United States counted 564,708 people sleeping outside, in emergency shelters, or in transitional housing on a winter night in 2015. About 15% of those counted were chronically homeless, including over 13,000 members of chronically homeless families.[49]

Like migrant workers, homeless workers (including the unemployed) are harassed and herded by police. An increasing number of cities in the United States have passed legislation making it illegal for homeless people, who have nowhere else to be, to perform life-sustaining acts — eating, sleeping, urinating, defecating, sheltering — in public.[50] The epigraph to this section has Marx describing advances in technology which connect people over ever further geographic distances as “the annihilation of space by time.” The radical geographer Don Mitchell has described the criminalization of homelessness as an example of another way in which capitalism annihilates space:

In city after city concerned with ‘livability,’ with, in other words, making urban centers attractive to both footloose capital and to the footloose middle classes, politicians and managers of the new economy in the late 1980s and early 1990s have turned to what could be called ‘the annihilation of space by law.’ That is, they have turned to a legal remedy that seeks to cleanse the streets of those left behind by globalization and other secular changes in the economy by simply erasing the spaces in which they must live.[51]

The short-sighted interests of capitalism and capitalists are best served by the propertyless workers it produces when those workers are relatively immobile and stuck competing for low wages. The policing, border regimes, and other mechanisms of control set around migrants and vagrants to keep them simultaneously homeless yet constrained work to satisfy those interests.

John Smith, author of Imperialism in the Twenty-First Century, has argued that driving wages even below the free-market value dealt with by Marx’s theory of exploitation — what Smith therefore refers to as “super exploitation” — through the dislocation and control of workers in developing countries has become the predominant method of increasing the surplus-value extracted from workers under global capitalism. “By uprooting hundreds of millions of workers and farmers in southern nations from their ties to the land and their jobs in protected national industries, neoliberal capitalism has accelerated the expansion of a vast pool of super-exploitable labor.”[52]

But while the scale of the global proletariat in the twenty-first century may be unprecedented, capitalism has never operated according to the free labour market it has imagined for itself. As the anthropologist David Graeber has noted:

the history of capitalism has been a series of attempts to solve the problem of worker mobility—hence the endless elaboration of institutions like indenture, slavery, coolie systems, contract workers, guest workers, innumerable forms of border control—since, if the system ever really came close to its own fantasy version of itself, in which workers were free to hire on and quit their work wherever and whenever they wanted, the entire system would collapse. It’s for precisely this reason that the one most consistent demand put forward by the radical elements in the globalization movement—from the Italian Autonomists to North American anarchists—has always been global freedom of movement, ‘real globalization,’ the destruction of borders, a general tearing down of walls.[53]

Marxists (following Marx himself) tend to view capitalism as a progressive development, as a powerful force of socialization and production. The effects of this stance can be seen in the Leninist and Stalinist industrialization programs conducted in the USSR and elsewhere which intentionally initiated processes of primitive accumulation and succeeded in reproducing, within a compressed time frame, both the horrors and the advances in technology which accompanied the more organic rise of capitalism in sixteenth-century Europe. Under this Marxist influence, socialism is sometimes reduced to a program of development, following Lenin’s own rather caricatured formulation that “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country.”[54] In the struggles against neoliberal capitalism, Marxists as advocates of progressive primitive accumulation have sometimes found themselves opposed to indigenous groups and other anti-capitalists who are often more concerned with preserving tradition and livelihoods in the face of the encroaching threat of capitalist development than with accelerating their own obsolescence.

David Harvey does an admirable job of describing and attempting to navigate these complications in The New Imperialism.[55] However, he narrowly skirts the longstanding Marxist predilection of presenting capitalism as a more beneficial force than it is. In his attempt at distinguishing between progressive and destructive forms of accumulation by dispossession, he notes that the position of women has been enhanced by factory work and that “Faced with the choice of sticking with industrial labour or returning to rural impoverishment, many within the new proletariat seem to express a strong preference for the former.”[56] Similar sentiment, formulated less carefully and more crassly as something like “sweatshops are good for the poor,” expresses a frequent talking point of neoliberal apologists. Even if it were true, it would only be true by an implicit assumption that there is no alternative to capitalism (a literal Thatcherite slogan) or by jumping from ‘best possible’ option to ‘good’ option without justification, a naturalistic fallacy.[57]

Factories are not completely lacking in social benefits, and the capitalist patriarchy of the factory can offer opportunities for independence many girls (especially) are not given in the feudal patriarchy of their villages. But it is likely not true in general that people prefer industrial impoverishment to rural impoverishment, at least not until rural subsistence becomes an impossibility due to privatization and the ensuing pressure to buy commodities, pay rent, and make credit payments. A recent randomized study conducted in Ethiopia which provided industrial jobs to participants (mostly young women who had expressed interest in such work) and then tracked them over the course of one year found that 77% quit their jobs and returned to informal work within that time: “these young people used low-skill industrial jobs more as a safety net than a long-term job, and […] self-employment and informal work were typically preferred to, and more profitable than, industrial jobs, at least when people had access to capital.”[58] That young women do not prefer to leave their family life to work unpleasant, dangerous, degrading, alienating, low-paying industrial jobs with long hours would be surprising only to a liberal (or perhaps Marxist) economist, but it is such unlikely preferences that are nevertheless repeatedly claimed in defense of industrialization.

The study also found that people with the means to become self-employed were usually successful at avoiding industrial work, which shines a hopeful light on microfinance and its entrepreneurial aims. But the threat remains for microfinanced work-from-home schemes (often targeted at housewives who need 'supplemental’ income) to become simply cheaper ways to [super]exploit rural poor without the overhead of a factory. An important detail when considering the Ethiopia study is that it was evidently conducted at a time when industrial wages in Ethiopia were not yet competitive with the informal sector, which explains why the participants were able to quit their jobs so easily. In the report, the researchers who conducted the study naively wonder why the firms they worked with did not try to combat turnover by paying higher wages. But of course factory owners know enough about maximizing profit to rely on subsidized non-market, coercive forces whenever they can. And as we’ve seen, the politics of global capitalism are characterized by policies that allow and encourage accumulation by dispossession — enclosing and privatizing traditional farmland, crushing informal local markets with cheap imported goods, saddling the under-employed with expensive debt, erecting border controls to prevent migrants from finding better conditions elsewhere. Factory owners in places like Ethiopia can count these policies to provide continued and increasingly reliable access to cheap labour without needing to pay a reasonable wage (and when workers then “choose” those jobs rather than starving in the rubble of the traditional and informal economies, we will hear again about how sweatshops are actually feminist social programs which are good for the poor).

The orthodox Marxist optimism toward capitalism and its violence is not shared by more libertarian socialist traditions. The anarchists and autonomist Marxists mentioned by Graeber in the above quotation, for example, view capitalism as the failure to abolish earlier class societies rather than as a necessary step toward that goal.[59] Especially relevant to this essay are the autonomist critiques, with roots in the feminist struggles of the 1970s, which expand Marxian categories beyond the factory to provide a class-conscious understanding of housework and reproduction. As Silvia Federici wrote in the introduction to Caliban and the Witch, her book exploring the role and persecution of women during the rise of capitalism, “Marx could never have presumed that capitalism paves the way to human liberation had he looked at its history from the viewpoint of women.”[60]

2. Housework

One could, even, start from the belated recognition of the importance of women’s labor to reimagine Marxist categories in general, to recognize that what we call “domestic” or even “reproductive” labor, the labor of creating people and social relations, has always been the most important form of human endeavor in any society, and that the creation of wheat, socks, and petrochemicals always merely a means to that end, and that—what’s more—most human societies have been perfectly well aware of this. One of the more peculiar features of capitalism is that it is not—that as an ideology, it encourages us to see the production of commodities as the primary business of human existence, and the mutual fashioning of human beings as somehow secondary.

“The Sadness of Post-Workerism”

2.1. Genesis

The capital in capitalism derives from the Latin root caput, meaning “head” as in “head of livestock.” The words cattle and chattel share that etymology and were once also used as general terms for movable property or wealth. The derivation makes sense: The important attribute of animals as a type of property is that they are productive: barring a catastrophe, an owner of livestock can expect the number of heads they own to increase with time as the animals reproduce; and since the rate of births will be roughly proportional to the total number of animals, the rate of increase will be exponential.

From an investor’s point-of-view, modern capital is a generalization of livestock which works on identical principles. An investor makes an investment, their invested money goes forth and produces additional value (as if reproducing on its own), and it then returns to the investor along with their share of the increase. But things are very different from the workers' point-of-view from whence capital does nothing productive on its own. It is only by applying human labour that capital can be made to produce wealth. And that capital, in the form of tools and other material inputs, was itself created or mined by workers. In turn, much of the newly created value will be taken by owners and re-invested into more capital to be worked. “Capital is dead labour which, vampire-like, lives only by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.”[61]

Capital does not reproduce autonomously like livestock, but people do. All economic wealth is the result of human labour, and all labourers are the result of the arduous work of human reproduction. Tracing this relation backwards reveals a motive for some of the most horrific organizing forces in our species' history: to control humans is to control the production of wealth, and to control young women is to control future, exponentially increasing wealth. From these two dynamics derive the various forms of exploitation and patriarchy as they’ve been invented and adapted by societies around the planet over the millennia.

The ancient Israelites had a myth about the origin of civilization: when the first human couple first disobeyed God, they were expelled from paradise to live a life characterized by wearing clothes, agriculture, the enduring anxiety of death, moral knowledge, separation from the divine, and most significantly to our current discussion, the sexual division of labour. In the version of the narrative recorded in Genesis 3, God says to the man:

cursed is the ground because of you;

in toil you shall eat of it all the days of your life;

[…]

By the sweat of your face

you shall eat bread

Class societies which are built on some form of economic exploitation have discovered a partial “solution” to this curse: make most people do extra work so that a small parasitic class may have bread for free. In pre-capitalist societies, these class distinctions are clear: everyone knows the master appropriates what the slave produces. Capitalism doesn’t change the fact that economic wealth is created by human labour, of course, or that bread must be bought with somebody’s sweat. But the extraordinary thing about capitalism is the degree to which it manages to obscure such a basic fact. The great innovation of wage labour is that it hides the underlying exploitation with the illusion of a voluntary and equal exchange of work for money.[62] The idea that it is money rather than work that produces wealth or that investors play a role equal (or even primary) to workers in the production process is always current in the ideology of capitalist societies. It wasn’t until Marx articulated his theories in the middle of the nineteenth century that philosophy could even offer a clear look behind the appearances of the wage system to reveal how profit is the result of paying workers less than what they produce, a tax cleverly hidden and extracted by paying as wages what labour costs rather than the full value it produces.

But to the woman in the myth, God gave this curse:

I will greatly increase your pangs in childbearing;

in pain you shall bring forth children,

yet your desire shall be for your husband,

and he shall rule over you.

The Hebrew word rendered in the above passages as both “toil” for the man and “pangs” for the woman is 'itstsabown (עצבון) meaning “worrisomeness, i.e. labor or pain: sorrow, toil.”[63] A translation which preserves the repeated word and so the generalization across the division of labour would have been to use in both verses the English word labour which has historically been used to describe specifically both the pain of tilling the ground and of childbirth. But 'itstsabown seems to be even more general than labour, indicating mental anguish as well as physical pain and is specific to neither manual labour nor childbirth. The word rendered “pain” in the next part of the line directed to the woman (“in pain you shall bring forth children”) is 'etseb (עצב), from the same root as 'itstsabown and with an almost synonymous meaning (in modern Hebrew it means “sadness”).[64]

A translation of the first lines which follows the underlying Hebrew more literally than most other English versions (taking the above and other lexical considerations into account) is provided by biblical scholar and archaeologist Carol Meyers:

I will greatly increase your toil and your pregnancies; (Along) with travail you shall give birth to children.[65]

Meyers uses this translation to argue her thesis that the pronouncement is fitting to the conditions of an emerging Israelite civilization during the early Iron Age (around 1200 BCE) when maintaining an existence in the thorny Canaan highlands would have given rise to an anxiety about underpopulation and the demand for women to contribute significantly to both food production as well as to caring for children. She also observes that though the division of labour and balance of power between the sexes varies greatly across societies, “The continuum of possible relative contributions of males and females to societal chores can be correlated with the status of women. […] Within certain parameters, societies in which women enjoy relatively high status are those in which women bear a quantitatively large portion of the roles which comprise the productive labor of the community.”[66]

In other words, according to the anthropological model espoused by Meyers, when women as a class perform both their maternal duties and contribute significantly to food production they enjoy a higher social status. However, because women are preoccupied with their pregnancies and domestic chores, they can never contribute to the material needs of society as much as men can (Meyers gives a maximum estimate of 60%:40% man:woman balance of contributions) so “women are never valued as a class more than men.”[67]

But as myth the etiological insight offered by the Genesis account is far more general than the specific circumstances in which it may have been developed. The Biblical account of woman’s daily suffering, especially clear in Meyers' translation, is linked to her biological specialization for childbirth beyond its specific, periodic pains. Among the general pains of childbirth is the domestic work it entails according to cultural norms. In most societies this work has included not only giving birth and caring for infants, but washing, preparing food, healing, making clothing, and gardening for the entire family. As a corollary, because women are tied to the home by their work, the tasks that must be done in the distant fields and forests — including farming, hunting, and fighting — traditionally fell to men for which toiling in the cursed land of the myth is a stand-in.

As in the case of the man’s plight to work the ground (which, as noted, can be seen as a consequent of the woman’s own plight), the general trajectory of human civilization has evolved from the configuration described in the myth — in which women suffer the pain of child birth and the bulk of the subsequent care work upon which all societies depend while at the same time being rendered subservient to their husbands — to develop versions which further intensify and mystify the suffering. This basic pattern in which women work twice and are valued less, a cross-cultural fact of modern societies and described by the early Hebrews as an originating characteristic of civilization, is the ancient foundation upon which today’s capitalism has been built.

Nineteenth-century anthropologists developed their own myths of the origins of family and women’s oppression. For several decades into the twentieth century, the ideas of Lewis Henry Morgan, a pioneering American ethnologist, became current in both America and the United Kingdom. Through his studies of the matrilineally-organized Iroquois tribes in New York, especially their kinship terminology which he believed held clues to their prehistoric kinship system, Morgan developed a theory of social evolution in which he attempted to reconstruct the universal family forms adopted by human societies as they advanced through historical stages of technological development. Morgan published the most complete version of his theory in 1877 as Ancient Society.

Marx and Engels considered Ancient Society to be an independent development and confirmation of their own materialist conception of history including the origin of class antagonism itself: “The first class opposition that appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamous marriage, and the first class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male. […] It is the cellular form of civilized society in which the nature of the oppositions and contradictions fully active in that society can be already studied.”[68] After Marx’s death, Engels set out to write a book to summarize Morgan’s findings and synthesize them with Marx’s economic social theory which was published in 1884 as The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

The most salient feature of Morgan’s conjectured history of kinship groups, as summarized by Engels, is that early societies were built around matrilineal families and matrilocal, communal households where women enjoyed high social status due to their important reproductive role and could count on the solidarity of their sisters and brothers in any dispute with a visiting husband. But then the gradual fall from this pre-pastoral Eden: With “the introduction of cattle breeding, metalworking, weaving and, lastly, agriculture,” it became possible to produce a sizable surplus of wealth.[69] These new methods of production, generally controlled by men, allowed old forms of social obligation to be replaced by purchase, made slavery useful on a wide scale and war profitable for the first time, and provided an impulse to convert the clan’s wealth into private property of the family while replacing matrilineal with patrilineal reckoning of descent.

The success of this patriarchal revolution dissolved the primitive communism of the matrilineal clans and gave rise to varying degrees of what Engels called the monogamous family which “is based on the supremacy of the man,” who alone has the right to divorce. The express aim of the monogamous family is “to produce children of undisputed paternity; such paternity is demanded because these children are later to come into their father’s property as his natural heirs.” The shift to a society composed of monogamous families was, in Engels' famous words, “the world-historical defeat of the female sex.”[70]

Some modern anthropologists accept matrilineal primacy and primitive communism, but other particulars are now known to be incorrect and the overall Morgan-Engels scheme is challenged on several grounds.[71] Still, Engels’s account remains compelling if only because it is an attempt to find the historical origins of the subordination of women within families and public society. It is easier to confront and undo a historically constituted arrangement than one that is presented as eternal or unchangeably “natural”. And whereas anthropologists have only interpreted culture, in various ways, the point is to change it.[72]

Morgan and Engels’s work on the family can be read in part as an attempt to provide a scientific explanation of the myths of prehistoric matriarchy found in many cultures (they both drew on Johann Jakob Bachofen’s very popular, at the time, Mother Right, which read those myths as history). But there is another, more sinister, interpretation of those myths which doesn’t rely on fragile anthropological evidence and, in fact, describes a process that can be observed to take place every day all over the world and for thousands of years. That is that myths of matriarchy, and male initiation rites which fulfill a similar role, are repeated narrations of the transition from the mother-dominated world of boyhood in the home to patriarchal manhood in public society. In this interpretation, myths of matriarchy work as a tool of education and socialization to help reproduce patriarchy and its existing sexual division of labour. “The myth of matriarchy is but the tool used to keep woman bound to her place. To free her, we need to destroy the myth.”[73]

Whatever their actual prehistory, patriarchal relations — including the control of and ownership rights to women and their fertility — are the prototypical organization for class societies and have been adapted quite well to serve the reproduction of capitalism and its workers. When factory production is thrust upon a population, the gender composition of its employed workforce follows a pattern of development in which the first employees tend to be (sometimes almost entirely) female, followed by a period of de-feminization, and finally, at least as observed in progressive capitalist republics, the re-entrance of women to the wider workforce at rates, in roles, and earning wages on a slow trajectory toward parity with men. The first two phases are especially pronounced in modern export-oriented manufacturing regions, made possible by global capital, where sweatshops on opposite sides of the planet must compete as sites of low wages.

The maquiladora system in Mexico, for example, began with an overwhelmingly female workforce. In the late 1960s, 90% to 95% of production workers were women, while supervisors and higher-paid technicians were mostly American men sent over from the parent companies. As late as 1975, women still made up 78% of the production line workforce (and almost 93% in border maquilas), but only 57% by 1998. Supervisory and technician jobs were increasingly filled by Mexican workers, but were more often given to men; if those positions are counted then the ratio of women to men drops to about 52% in 1998. By 2005 women accounted for only 44% of all maquiladora jobs (with new male hires still going disproportionately to supervisory and technician roles).[74] Similar trends can be seen among the ‘factory girls’ of China’s Pearl River Delta and other Asian manufacturing zones.

Marx was aware of the first stage of this trend in industrializing Europe, which he explained by pointing to mechanized factories which allow the employment of “workers of slight muscular strength” so that the “labour of women and children was therefore the first result of the capitalist application of machinery!”[75] While that might explain why capitalists could employ women and children on a large scale,[76] the reason they did, and did so eagerly, was because women and children made up a vulnerable segment of the population which could be more intensively and reliably exploited. Men not only had more pride, education, and political clout, they were also more likely to already be organized into labour associations which opposed the reduction of wages accompanying automation. Marx also noted this latter point, that women were found by capitalists in a more exploitable position. As an example he quoted the testimony of a member of parliament regarding an owner of power looms who employed exclusively women and girls and who gave “a decided preference to married females, especially those who have families at home dependent on them for support; they are attentive, docile, more so than unmarried females, and are compelled to use their utmost exertions to procure the necessaries of life. Thus are the virtues, the peculiar virtues of the female character to be perverted to her injury — thus all that is most dutiful and tender in her nature is made a means of her bondage and suffering.”[77]

While the idea that women have “peculiar virtues” which can be used against them persists, most sweatshop owners are not as forthright as the Victorian power loom employer quoted above. From the textile factories of Southeast Asia to the assembly lines of Mexican maquiladoras, employers almost always justify their preference for vulnerable women in the rhetoric of naturalization rather than acknowledging the desperate financial situation of the girls they hire: women (and children) make good factory workers because they have “nimble fingers” or are naturally “dexterous” and “diligent,” etc.

But Marx thought the effect of mechanized factories preying on women and children would be the destruction of the working-class family. What happened instead was that men began to make up more of the unskilled industrial workforce while women were relegated back to the informal/service sectors and unpaid domestic work. Thus industrial society — in nineteenth-century Europe as well as its subsequent expansions driven by ongoing rounds of primitive accumulation — swings from extensively exploiting women as the cheapest available labour to a norm in which women are excluded from the factory and are “relegated to a condition of isolation, enclosed within the family cell, dependent in every aspect on men.”[78] It has never actually been the case that most women could afford to do only housework, but that was nonetheless the ideal during the periods in which capitalism claimed to offer a ‘family wage’. The economic conditions which produce these swings include growth outpacing the supply of women — especially as the initial population of women and children are worn out and used up while the survivors begin demanding more respect and legal protection — and the reduction of real wages in the higher-paying sectors making factory work more attractive to unemployed men. Political and moral movements also activate to combat the erosion of family values by industry.

The first phase, feminization of industry, works to destroy whatever is left of pre-capitalist family livelihood, while the second, housewifization, then works to integrate proletarized women into roles as reproducers of the capitalist workforce. The arrangement resulting from housewifization protects women and children from the abuse of factory life, protects the wages of men and their privileged position in the home as the breadwinner, and perhaps most importantly protects the family as an effective means of producing children, vessels of future labour-power, and therefore of reproducing capitalist society. The fact that this arrangement preserves traditional male privileges, a tacit compromise with working-class men who are rewarded with a ‘family wage’ and the possibility of a captive housekeeper, suggests the possibility that men, even Marxists and militant labour activists, might choose a symbiotic relationship with capital in favor of housewifization and other patriarchal perks. As Heidi Hartmann remarked in noting this pitfall of relying on men to lead the fight against capitalism and the oppression of women: “Men have more to lose than their chains.”[79]