Some thoughts on Kiva's interest rates

1. Two Misconceptions About Kiva

Kiva Microfunds is a nonprofit organization whose website allows users to provide money toward filling small personal and business loans to individual borrowers around the world. The stated mission of Kiva, whose name is a Swahili word meaning unity or agreement, is “to connect people through lending to alleviate poverty.”

Users of the website browse profiles of borrowers and select those to whom they wish to lend. Each profile includes the borrower’s location, some brief biographical information (usually including a photograph), and a description of what the loan will be used for. Users can then lend as little as $25 to a borrower, which is pooled with money from other users to reach the full loan amount. When the loan is repaid, the user’s account is credited back the amount they gave which can then either be lent to another borrower, donated to Kiva itself, or withdrawn. In its first ten years of existence (October 2005—October 2015), Kiva’s users lent $774 million to 1.8 million borrowers (75% of whom were women) in over 80 countries.[1]

The goal is to improve the quality of life in developing and conflict-torn regions where it is hoped that entrepreneurs can make effective use of even very small, expensive loans. The loans are disbursed by Kiva’s field partners called microfinance institutions (MFIs). Despite its founders' original intention of allowing users to realize gainful returns on their loans, Kiva itself does not collect interest on loans, and Kiva’s users do not receive any interest on repaid loans.

While the concept behind Kiva is simple — use a website to crowdsource cheap credit to subsidize MFIs operating in poor neighborhoods — the way it is presented can be confusing and tends to result in two misconceptions:

- That Kiva users lend money directly to individual borrowers

-

Because the Kiva website is built around the biography-oriented borrower profiles, it is easy for users to assume that the money goes directly to the borrower after the loan is filled. Both assumptions are wrong for most loans. In fact the money goes to intermediary MFIs who usually disburse loans to borrowers even before their profiles are posted to kiva.org. By the time Kiva users have filled the loan amount, MFIs have not only already disbursed the loan but have likely started collecting payments (and interest) from borrowers.

So Kiva is not a direct person-to-person lending system. Kiva users are in fact lending risk- and interest-free money to Kiva’s partner financial institutions, not to individual borrowers.

The Kiva website was once even more misleading about how disbursements worked, but after David Roodman of the Center for Global Development published an editorial titled “Kiva Is Not Quite What It Seems” (October 2009) which gained significant attention online, Kiva updated their “How Kiva Works” page to make it clear that loans are pre-disbursed.

- And that borrowers are not charged interest on loans received through Kiva

-

Because Kiva itself is nonprofit and presents its operations as philanthropic, and because users do not receive interest on the money they lend, users might easily assume that borrowers are not charged interest. That is also an incorrect assumption. Most of Kiva’s partner MFIs do collect interest and other fees on the loans, sometimes at very high rates, and sometimes acting as explicitly for-profit investor-owned banks.

2. What Are the Interest Rates Charged by Kiva’s Partners?

Kiva does not directly provide information on interest rates for most individual loans. Instead, it lists two measures of field partners' performance which can be used to roughly indicate the average annual interest rate on that institution’s products and how much profit those rates produce:

-

Portfolio Yield is the primary measure of the cost of loans from a given lender and can be treated roughly as the annual interest rate. Portfolio yield is defined as all interest and fees paid by borrowers to the field partner divided by the average portfolio outstanding during any given year.

-

Profitability (Return on Assets) is the field partner’s net income divided by its total assets. It indicates how efficiently a field partner turns its investments into profit.

| Kiva has started listing a calculated APR for some of its partners. They’ve introduced an “Average Cost to Borrower (PY/APR)” metric which displays either the Portfolio Yield (PY) or Average Percentage Rate (APR), whichever is available. |

According to the Kiva website the average Portfolio Yield for all of its field partners in January 2016 was 29.09% (down from 35.21% in January 2010), but some of its field partners have yields near 100%. In 2010 the charity evaluator GiveWell surveyed one of Kiva’s field partners, MLF-Malawi, and reported that the actual APR on its most popular loan was 144%-149%.[2]

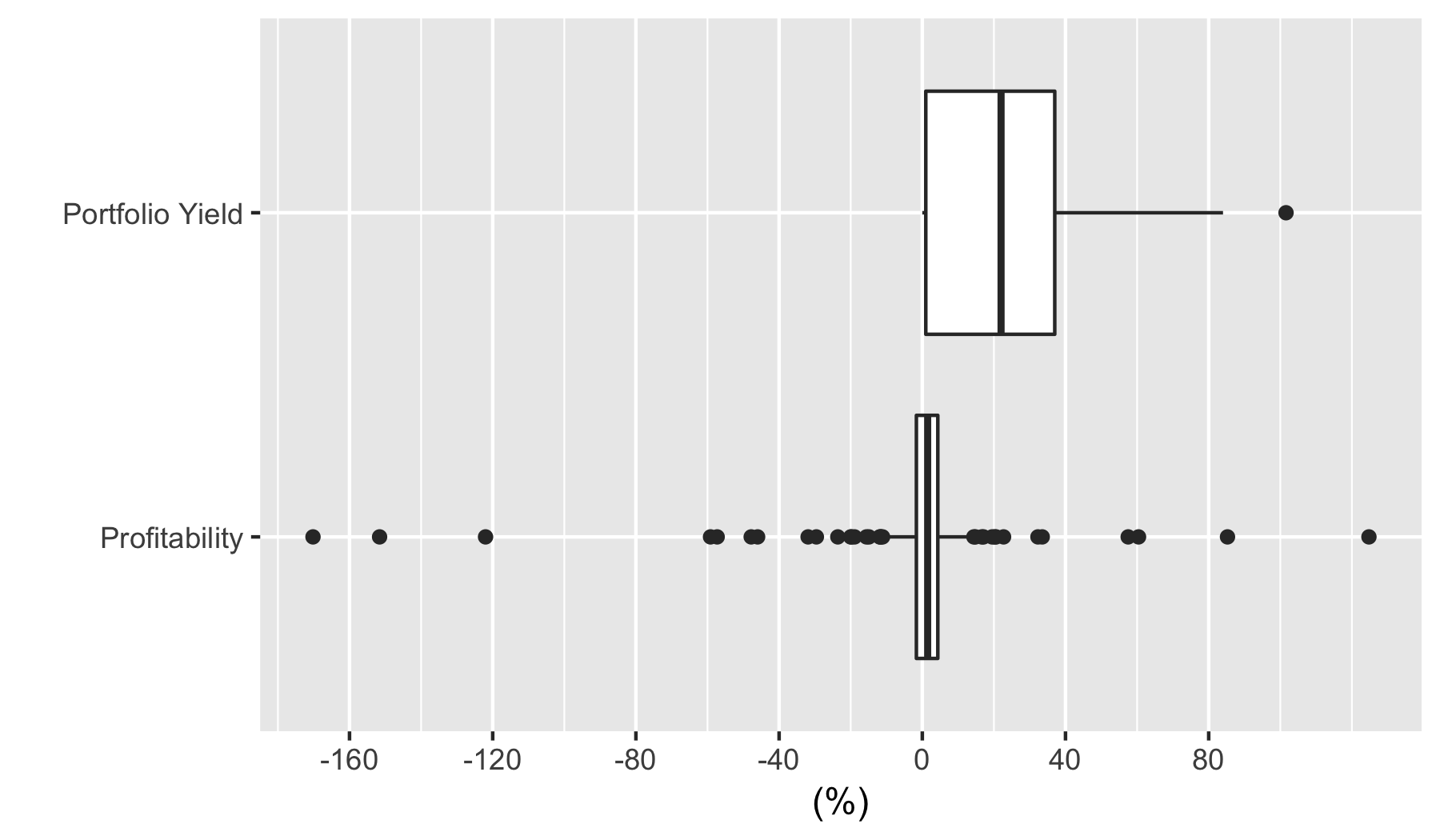

As of January 2018 Kiva provides both Portfolio Yield and Profitability for 196 out of its 270 active field partners. The table and graph below summarize the range and distribution of those metrics.[3]

| Minimum | 1st Quartile | Median | Mean | 3rd Quartile | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portfolio Yield |

0% |

0.975% |

22% |

23.839% |

37% |

101.6% |

Profitability |

-170.2% |

-1.653% |

1.5% |

-0.262% |

4.333% |

124.76% |

As a comparison to interest rates in countries with established and widely available financial services, the average credit card APR in the United States is about 15%,[4] and the maximum allowed interest rate on loans backed by the Small Business Administration is 8.75%.[5]

2.1. The problems with ‘Portfolio Yield’

The Portfolio Yield indicator is the best available proxy for the actual annual percentage rate (APR) for most loans disbursed by Kiva’s field partners. Portfolio Yield was actually introduced by Kiva in 2009 to replace an even worse proxy for interest rates.[6] Microfinance Information Exchange (MIX), a non-profit organization, sampled several MFIs and found an adjusted Portfolio Yield to be within five percent (not percentage points) of the reported APR.[7]

However, in the MIX analysis the Portfolio Yield indicators were adjusted upward to account for defaulted and at-risk loans still on the books (which inflate the portfolio value and so deflate the reported Portfolio Yield). In addition to overvalued portfolio, the Portfolio Yield can easily underestimate the actual APR of microloans for two other reasons:

-

Many of the microfinance institutions partnered with Kiva require borrowers to save a portion (usually around 20%) of the loan they receive. This requirement is known in the microfinance world as “forced savings.” Borrowers from MFIs which use forced savings are effectively paying interest on a larger loan than they receive, so the Portfolio Yield in those cases will be misleadingly low.

-

Because the Portfolio Yield is calculated based on an institution’s average outstanding portfolio, it will tend to reflect the larger (usually cheaper) products offered by that institution rather than being an accurate estimate of the (almost always higher) rates on the tiny loans provided to the struggling rural borrowers featured on Kiva.org. The MIX report identified this (the use of the wrong APR to represent an institution’s microfinance loans) as the main reason Portfolio Yield and APR diverge.

So the nominal interest rates suggested by the Portfolio Yield of an MFI, which can be outrageously high, in many cases significantly underestimate the interest actually charged to microfinance borrowers.

Hugh Sinclair, author of Confessions of a Microfinance Heretic, wrote an article titled “What’s Wrong With Kiva’s Portfolio Yield Statistic?” exploring both of these (and other) problems with Kiva’s Portfolio Yield metric. He compared the actual APR for a sample of loans from ten of Kiva’s field partners with the Portfolio Yield reported by Kiva: for every MFI he looked at, the APR on most of the loans was higher (sometimes as much as double) the reported average Portfolio Yield.

So why doesn’t Kiva require MFIs to state the actual cost of loans made using Kiva money rather than relying on the oblique “Portfolio Yield” figure? Sinclair thinks it is because if people saw the actual interest rates collected on loans they are subsidizing then they would think twice before using Kiva:

Kivans like to believe they are helping the poor, and in order to achieve this Kiva needs to provide them with minimal, but reassuring information. Some nice photos, a little story, and as favourable an impression of the actual interest rates as possible, as this is an emotive topic that will irritate many Kivans. They can get away with rates of 30%, 40%, even 50%, but they have to avoid rates which will raise too many questions, and by citing a statistic known to be deeply flawed, but reassuring the Kivans, is the best way to do this.[8]

2.2. The use and difficulties of ‘Profitability (Return on Assets)’

While the high rates charged by some of Kiva’s partners are a bit shocking and look outright usurious on first sight, Portfolio Yield alone doesn’t indicate whether the interest being collected is exploitative. Those high rates could reflect the actual costs of administering credit in some regions of the world. Small loans are more expensive because fixed costs tend to dominate the price. And some regions have high inflation, poor or non-existent infrastructure, difficult to reach populations, or high crime and other instabilities, all of which contribute to the cost of credit.

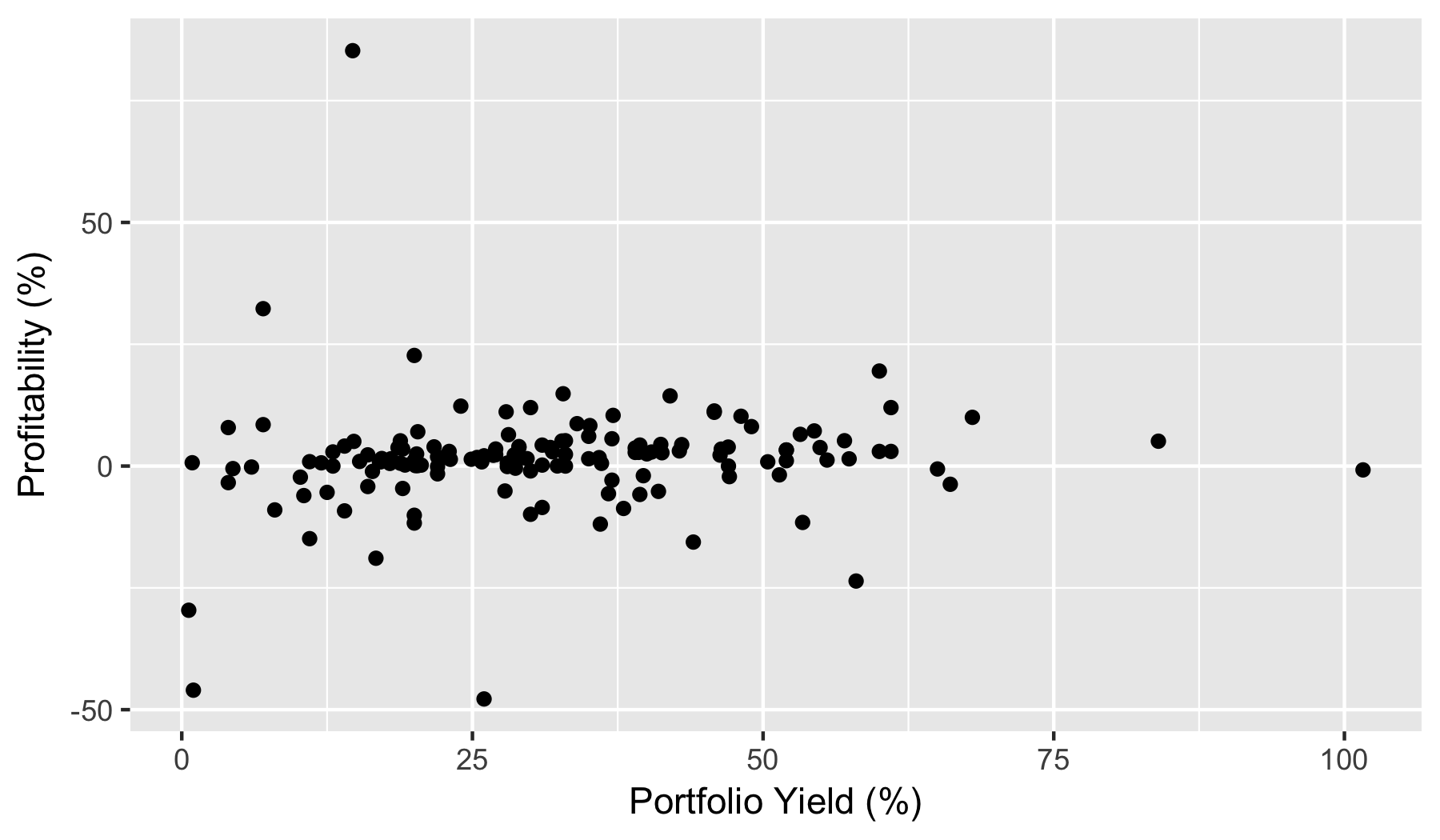

If high interest rates were simply the result of price gouging due to lack of competition, then we’d expect that MFIs which charge high rates would tend to have correspondingly high profitability. However, as illustrated in the graph below of Profitability plotted against the Portfolio Yield for all 149 MFIs (as of January 2018) with nonzero Portfolio Yield and available Profitability data, there is no such correlation (the Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.09).[3]

A 2013 report based on a sample of 193 MFIs (none necessarily partnered with Kiva) gave similar results but found a slightly negative correlation between return on equity and portfolio yield (r = -.117). The author of the report hypothesized that the negative correlation, indicating that more profitable MFIs charge lower interest rates, is the effect of MFI lifecycle stages: young MFIs try to reach financial stability by charging high rates and fees while mature MFIs can afford more competitive rates.[9]

In any case, the lack of correlation between Portfolio Yield and Profitability shows that at least some markets are competitive, though likely very geographically uneven. We might hope, then, that even if we concede high interest rates are a necessary evil in some regions to cover operating costs, we could use the Profitability metric alone to identify MFIs that are overcharging for loans (say, try to avoid giving to MFIs who make more than 15% on their assets). Unfortunately, as is noted in the next section, the Profitability indicator seems to be rather noisy and unreliable as an indicator that an MFI is overcharging (or undercharging) for its products.

In addition, it should be kept in mind that low profitability can be an indicator that an MFI is struggling with internal inefficiency including under-utilized investments, over-paid executives, and fraud (none of which are especially unheard of in the microfinance sector).

Other metrics Kiva provides that can help here are the Default Rate, Delinquency Rate, and Loans At Risk Rate. Field partners which have trouble collecting repayments may be charging more than their clients can afford.

2.3. MIX Market data

In addition to the information provided by Kiva itself, financial data about many of Kiva’s partner MFIs can be found on MIX Market (themix.org), an online clearinghouse for microfinance information run by the World Banks' Consultative Group to Assist the Poor. The data available on MIX Market is largely self-reported but claims to be independently reviewed and includes many more indicators than Kiva provides (including a portfolio yield figure which has been adjusted for inflation). Unfortunately, in June, 2016, while I was doing research for this essay, the MIX Market website was restructured to commercialize most of its data and publications behind a paywall making future research efforts using MIX datasets prohibitively expensive. Prior to the redesign, the MIX Market profile for Kiva provided a convenient list of MFIs currently and formerly associated with Kiva.[10]

In a weblog entry mourning the change, Phil Mader notes that the privatization of the MIX Market data “mirrors one of the darker trends in microfinance as a whole, where institutions are first set up with public or charitable money and supported for years (MIX was funded with millions of dollars in charitable, tax-deductible donations), but then are turned onto a revenue-maximising, commercial course, confronting their users with a hard-nosed commercial lender. Even though in practice this restructuring often fails to yield truly commercial returns (and behind the scenes the institution continues to be supported with soft money) the beneficiaries still must deal with what poses as a for-profit business, stripped of the more ‘social’ promises that lured them in.”[11]

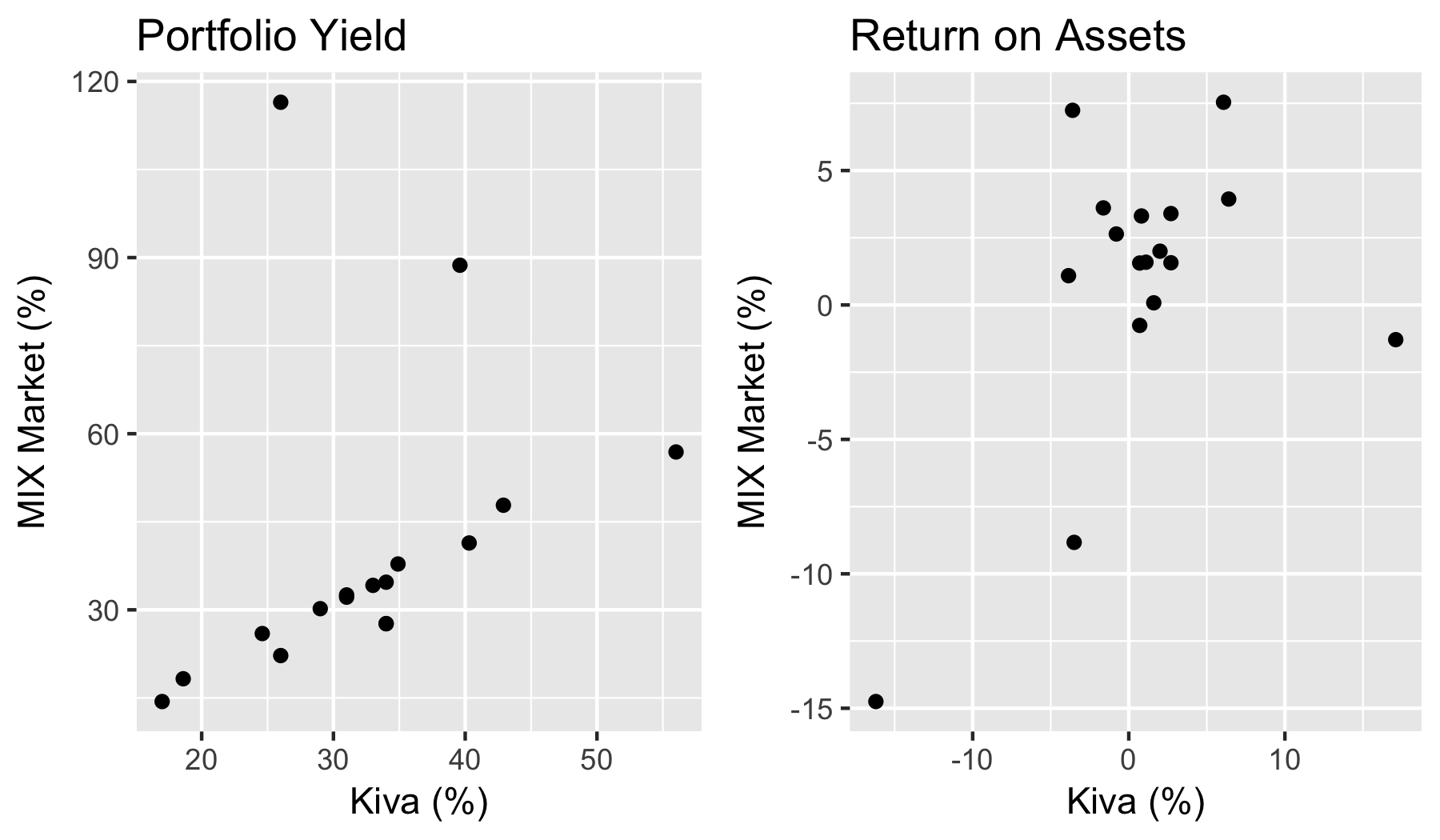

One issue in trying to assess an MFI’s financial characteristics is that the data reported by Kiva is sometimes very different than the data provided by MIX Market. To get an idea of how well the available data agrees, I sampled[12] the Portfolio Yield and Return on Assets indicators from both Kiva and MIX Market for several MFIs and plotted them in the figure below.[3]

While both sources tend to report similar Portfolio Yield figures (left graph), Kiva’s numbers can occasionally vary greatly from MIX Market’s. When the two obvious outliers are ignored, the correlation coefficient is nearly linear (r=0.96). In fact Kiva actually uses MIX Market data directly when reporting Portfolio Yield for some of its field partners, so that strong correlation is expected.[13] I do not know if there is a list of which partners Kiva uses MIX Market data for and which it calculates itself.

The Return on Assets figure (right graph), on the other hand, is much less consistent between Kiva and MIX (r=0.52).

I suspect the main cause of the discrepancies between the data reported by Kiva and MIX Market is timing: each organization receives and releases information from the MFIs on different dates (the plot above is based on the most recent data from both Kiva and MIX at the time of retrieval — but they aren’t necessarily updated at the same time). If that’s the case, then it indicates that the reported Return on Assets of MFIs tend to be rather volatile, which is another reason the Profitability metric may not be of much use in identifying non/exploitative MFIs.

2.4. Finding good lenders on Kiva

Keeping the limitations of Kiva’s metrics in mind, the best strategy a Kiva user can adopt in order to find loans from a good MFI on Kiva.org depends on their humanitarian philosophy: a user who is concerned that high interest does more harm than good should seek out loans through partners with low Portfolio Yield; a user who is most concerned about exploitation should look for partners with low Profitability; a user who wants a balance of sustainability and humanitarian efficacy might look for partners with low Portfolio Yield and moderate Profitability; etc.

The best way to explore individual loan offerings is to use Kiva’s lending tool (https://www.kiva.org/lend). As part of a June 2016 redesign, Kiva implemented improved filtering of their lending tool including the ability to filter based on “Average cost to borrower” (Portfolio yield, APR, or MPR, whichever is available) and “Profitability.”

Unfortunately Kiva does not provide the option to sort their field partners table by Portfolio Yield or Profitability. But they do helpfully provide field partner information through a programmable web interface. I used that service to build KivaSort (https://kivasort.americancynic.net/) which provides a fully sortable and filterable table of Kiva’s field partners.

By default KivaSort displays field partners with the lowest Portfolio Yield at the top to facilitate finding inexpensive lenders. But in order to illustrate and briefly investigate the high interest rates charged on some Kiva loans, the table below lists the active field partners with the highest Portfolio Yield (as of January 2018).

| Name | Portfolio Yield | Profitability | Country | Default Rate |

|---|

2.4.1. Example: Thrive Microfinance

If we read the Kiva profile for the MFI second from the top of the list of field partners with the highest Portfolio Yields, we learn that Thrive Microfinance is an independent MFI in Zimbabwe which lends exclusively to women using the group loan approach (in which small groups take out a loan collectively and keep each other accountable for payments).

Note that after suffering record hyperinflation from 2007—2009 (by the time the central bank stopped issuing currency, prices were more than doubling every 25 hours),[14] Zimbabwe stabilized prices by abandoning its national currency and switched to the US dollar. During most of 2014, Zimbabwe was experiencing slight deflation caused by a shortage of cash. That means the credit provided by Kiva was all the more valuable to Thrive, and its loans that much more expensive than their nominal rate.

The main reason Thrive charges so much for loans is apparently because they provide four weeks of mandatory training to borrowers before disbursing a loan. There is a note from Thrive addressing the high interest rates on their Kiva profile which concludes, “Even though we could reduce the interest rate if we reduced the amount of training, we do not believe that it is in our borrowers' interests to do so.” That rings hollow to me: why not provide cheaper loans and then sell training to the groups who find that service valuable enough to pay for it?

2.4.2. A note on Islamic banking

Allah will deprive usury of all blessing, but will give increase for deeds of charity: For He loveth not creatures ungrateful and wicked.

Islam has always had a healthy suspicion of exploitative increase (called riba in Arabic). As a result, financial service providers including MFIs partnered with Kiva which conform to sharia law are forbidden from charging interest on loans.[15]

Islamic financial institutions have developed some creative methods of working around the prohibition on interest by recasting loans as either joint ventures or normal trades, neither of which involve interest in a strict sense. Popular schemes include:

-

Mudarabah - where a bank provides capital and then shares the profit/loss at an agreed upon proportion with the entrepreneur.

-

Murabaha - where a bank buys an item, and then sells it at a higher price to the “borrower” who buys it from the bank in installments. This is the most popular Islamic financial instrument because it provides a predictable profit margin for the lender, though insofar as it is an attempt to hide financial interest (riba al-qurud) as merchant profit (riba al-buyu) it is arguably a violation of sharia (at least in spirit).

Islamic financial services dull the dangerous edges of traditional interest: if a borrower becomes unable to repay a loan, at least they do not become hopelessly burdened by ever-compounding interest. For that reason even devious implementations of murabaha will tend to be less exploitative and damaging than capitalist credit. However, it is a mistake to think that because Islamic loans are “interest free” they are also necessarily non-profit. Islamic banks still leverage their capital to profit from the work of borrowers. Furthermore, because Islamic banks take on more risk than traditional banks, loans based on murabaha generally require upfront collateral for the loan amount so that even without the spectre of compounding interest, Islamic loans can still pose a serious risk to families and poor entrepreneurs whose ventures fail.

The same metrics used to evaluate other field partners can be used to evaluate Kiva’s sharia-compliant field partners. For example, at the time of this writing Kiva’s long-time partner Al-Amal Microfinance Bank has a Portfolio Yield of 33.1% and a Profitability of 11.1%. Another example is Jerusalem Interest-Free Microfinance Fund Limited which is operated by volunteers and disburses loans at 0%, with a profitability of 17.1% (presumably its income from donations).

3. Philanthropy or Business?

It is immoral to use private property in order to alleviate the horrible evils that result from the institution of private property. It is both immoral and unfair.

The Soul of Man Under Socialism

3.1. Kiva’s origins: an accidental charity

Kiva was founded in 2005 by Matt Flannery and Jessica Jackley, a husband-and-wife team working out of San Francisco. They developed the first version of the Kiva.org website while Flannery was employed as a programmer at TiVo and Jackley was employed at the Stanford Business School (where she attended a lecture by Muhammad Yunus which ignited the initial spark of inspiration). Two years after launching, Flannery published a retrospective about Kiva’s origins and development called “Kiva and the Birth of Person-to-Person Microfinance.”[16]

In that article, Flannery described how even in the early days of Kiva there was a fundamental tension about “whether it was better to be seen as a charity or as a business.”[17] Neither Kiva nor its users have ever earned interest on the loans facilitated by the website, but that charitable nature is more an accident of history (encouraged by the bureaucratic hurdles erected by the SEC) than the design of its founders.

The original plan was to charge MFIs interest on Kiva-financed loans, and then share a portion of that interest with users:

I architected the database, software, and user experience around the idea of returning interest to users. There was never any question that we wanted interest rates on the site.[18]

After grudgingly settling on the interest-free approach for the first two years, Flannery wrote that “we would still like to realize our original vision of having interest rates on the site. The fact that we had to remove them is a sore spot with me […] Kiva thus continues its effort to allow our partners to post businesses to the site with interest rates attached.”[19]

3.2. Charity for whom?

Kiva’s founding tension was resolved by keeping Kiva itself purely charitable, supported exclusively by donations and grants, but partnering it with remote field partners who charge interest. That way the SEC was satisfied and the dirty business of collecting interest from people with no money was pushed to a more comfortable distance from the users of Kiva’s website.

But the impedance-matching function of Kiva, which converts interest-free loans made by Kiva’s users into interest-bearing loans collected by microfinance institutions, understandably produces a cognitive dissonance in its users. That double nature of loans given through Kiva, which are simultaneously charitable credit for MFIs and expensive debt for poor borrowers, is the source of the misconceptions I outlined in the first section of this essay, and it raises a question at the heart of the matter: who benefits from the free credit raised by Kiva? Does the incidence of Kiva users' charity fall mostly on the borrowers they intend to help? or does it fall more on the MFIs who accept the free credit and then turn around and loan it for gain to those borrowers?

Profitability among Kiva’s field partners tends to be rather modest (suggesting that Kiva prefers partners on the charitable/non-profit as opposed to self-sufficient/commercial side of the spectrum): over three-quarters of currently active field partners have a Profitability at or less than 4.3%. By comparison, one report that looked at interest rate data from hundreds of MFIs (not limited to, or necessarily including any, Kiva field partners) over seven years found that three-quarters of MFIs in 2011 had a rate of profit up to 20%. That same report noted that if every MFI set their interest rates to their break-even point (so that profits = 0), then the average interest rate would fall by only 2.6 percentage points (in other words, even if every MFI were non-profit, interest rates would still be quite high in many cases).[20] That finding underscores the fact that microcredit is simply expensive.

The efficacy of microfinance at alleviating poverty has been a matter of research and debate since Muhammad Yunus founded the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh in 1983 (Yunus and the Grameen bank were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006). The early anecdotal reports of success and the prospect of a business-friendly cure to poverty created an increasing excitement around microfinance for over two decades. But in recent years expectations have sobered.

In the past five years or so several rigorous studies which use a randomized method to compare the effects of microfinance on borrowers have appeared in the academic literature. The result of one recent survey of six such studies found that “The studies do not find clear evidence, or even much in the way of suggestive evidence, of reductions in poverty or substantial improvements in living standards. Nor is there robust evidence of improvements in social indicators.” But the same survey also found “little evidence of harmful effects, even with individual lending […] and even at a high real interest rate.”[21]

Kiva performs a degree of due diligence and monitoring of the MFIs it chooses to partner with which provides some protection against abuse. The measures Kiva uses to evaluate field partners developed out of some hard-learned lessons. In their first four years of operations they discovered six “situations involving severe fraud,” including one involving their very first partner, a Ugandan man named Moses Onyango, who was so instrumental in getting Kiva started that he is sometimes referred to as the third co-founder.[22]

Among the MFIs Onyango signed up as partners in Kiva’s early days was one he founded himself, the Women’s Initiative to Eradicate Poverty (WITEP). It turns out that not all of the WITEP borrowers were real: some loans were being disbursed in the names of fictional people and pocketed by Onyango. Due to Uganda’s unresponsive legal system, Kiva never recovered the stolen money (but they did pay back Kiva.org users out of their own expense account, as well as maintain a policy of transparency about the fraud when it was discovered).

The kind of fraud Onyango perpetuated is not particularly worrying. He used the stolen money to buy a house for his family (and he was so grateful to Kiva for its influence on his life that he named his new son Matthew Flannery Onyango). What Onyango did was to cut out the interest-charging middleman and transform Kiva into the version of itself that users imagine it is: they lent money, helped out a Ugandan family, and got repaid.

Far more worrisome are legitimate MFIs who might use Kiva’s website as a place to sell feel-good stories to naive Americans for free capital with which they can go about their business of robbing the poor. It strikes me as much less likely that Kiva would discover and terminate its partnership with MFIs who overcharge borrowers, and in fact Kiva’s entire structure of funneling interest-free credit to interest-charging lenders almost encourages it.

As an example consider the case of Kiva’s former partner in Nigeria Lift Above Poverty Organization (LAPO). In 2010 the New York Times published an exposé about microfinance interest rates which specifically mentioned the high rates and forced savings of LAPO.[23] Kiva had initially defended the interest rates and high profitability of LAPO with its usual explanations (inflation, high operating costs, and the need for sustainability), but then after further investigation prompted by the media attention decided to terminate the partnership. LAPO overwhelmingly targeted women with its high-interest loans. The LAPO incident doesn’t exactly breed confidence in Kiva’s other partners who have not been investigated by journalists.[24]

3.3. Kiva’s apology

To questions about the high interest rates charged by its field partners, Kiva has responded by pointing to the high costs of administering microloans, emphasizing that they annually evaluate each partner “to ensure that there is a sound justification for each relationship,” and that they are continuing their efforts to bring in more charitable and 0% lending partners.[25]

In his article, Flannery also outlined a justification for the proposed collection of interest on loans to the global poor. He rejects pure charity, what he calls the benefactor relationship between people in developed and undeveloped countries, because “recipients resent benefactors even as they consume the aid.” He also rejects the defeatist notion that poor people cannot be helped, what he calls the colonizer relationship, because it is just the other side of “the same destructive mentality” as the benefactor. To these dialectical endpoints he applies a liberal dose of Silicon Valley Logic and derives the perennial insight that the best way to help poor people is to find a way to make money off of their circumstances. He calls this the business relationship, from which he formulates the precept that “interest rates, which turn a charitable relationship into a business relationship, empower the poor by making them business partners.”[26]

Invoking the concept of colonizer without any discussion or hint of awareness about actual colonialism or the socioeconomic context within which microfinance works is emblematic of Kiva’s tone-deaf approach to structural issues. This decontextualization is also inherent to the way the Kiva website packages and presents borrower profiles by “displacing them from local contingencies” thus providing to lenders a ‘flat’ and placeless perspective on development and poverty. “By obscuring the geographic contexts of microlending and borrowers, Kiva.org squanders an essential opportunity to engage the public with the ongoing conversation about poverty, debt, development, and the roots of contemporary inequality.” And the faux equality presented by Flannery’s “business relationship” obscures the differentials of wealth between the site’s lenders and borrowers. “Kiva not only renders its own workings unproblematic, but also justifies the worldwide expansion of micro-credit by much larger conventional aid and financial organizations.”[27]

Of course Flannery’s “business relationship” has never been unambiguously achieved by Kiva. The tension between philanthropy and business remains, and is in fact what is attractive to users of the platform. By promising a way for users to help the global poor without personal gain to themselves and without just giving money away, Kiva harmonizes the warring moralities of compassion and fiscal responsibility.[28] By blurring the differences between lenders and borrowers to maintain the illusion of person-to-person business deals,

Microfinance makes poverty in the global South comprehensible to the (primarily Northern) middle and upper classes by proposing a solution on terms that they can understand and identify with […] While their circumstances and constraints remain fundamentally different, the rich and the poor are seemingly aligned in the microfinance narrative through their shared identity as subjects of finance.[29]

In 2009 Flannery wrote a second retrospective for Innovations in which he expressed his lingering unhappiness that Kiva was not generating profit for comfortable Americans (who make up most of Kiva.org users) off of the hard work of poor women in remote agricultural villages (who make up most of Kiva’s borrowers): “I repeatedly tried to get the interest rates back on the site. […] To me, taking the rates off the site was an accident and I was determined to undo that temporary concession.”[30]

Fortunately, Flannery was never successful in his efforts to turn Kiva into a for-profit lending platform which would have had the effect of making loans targeted at the global poor even more expensive while sucking more wealth out of impoverished regions. In 2015, after serving as Kiva’s chief executive officer for ten years, he stepped down (but remains on the board of directors) to co-found the for-profit Branch International. Branch provides a branchless banking service (based on Vodafone’s M-Pesa) which allows people in Kenya to use a mobile phone app to receive small loans. Branch appears to determine credit worthiness and interest rates on an individual basis by an algorithm (which looks at borrowers' Facebook profiles, among other sources of data). By July 2017 Branch is reported to have disbursed $35 million (KSh3.63 billion) in loans to its 350,000 users. Interest rates start at 163.2% per year, and can get as low as 14.4% for users with the best credit rating.[31] No doubt this new enterprise provides Flannery with better opportunity than Kiva to more directly “empower” cash-strapped sub-Saharan workers.

3.3.1. Direct and interest-free: Kiva’s future?

In the final analysis, putting questions of profit and exploitation aside by assuming that MFIs operate efficiently and at some optimal balance between charity and sustainability, the root question which confronts the Kiva user is whether giving poor women in Zimbabwe expensive debt is a good way to help them — and if it is not, then what else can someone on their computer in a rich Western country do to help?

Fortunately Kiva has a few initiatives in the works which may help side-step these difficult questions in the future. In 2013 they launched Kiva Zip, a pilot program which offered loans directly to entrepreneurs (without an intermediary MFI) in the United States at 0% interest and without any credit score requirement. In 2016 the Kiva Zip program was integrated into the main Kiva website as Kiva U.S.[32]

In the summer of 2016 Kiva also announced the Direct to Social Enterprise program which provides interest-free loans directly to medium-sized enterprises (too big to be customers of MFIs and too small to benefit from commercial loans), which has brought the benefits of Kiva Zip to countries outside of the United States (albeit on a person-to-enterprise rather than person-to-person model). I haven’t found a complete list of participating social enterprises, but at least a partial list can be found by searching KivaSort for field partners whose names contain ‘direct to’.[33]

4. Deeper questions

On one hand the demographic and geographic distributions of Kiva’s borrowers and lender-users, wherein sympathetic people in parts of the world with extra money are providing charitable loans to people in parts of the world with not enough money, are not surprising. Those are exactly the sort of relationships Kiva exists to facilitate per its mission statement, after all. But Kiva’s entire model of microfinance takes for granted that there are a great number of women and peasants at the developed world’s periphery who are in desperate need of financial services without attempting to explain why the world’s wealth has become so stratified by lines of geography and gender, and without any introspection into its own role in the greater processes of global capitalism arising from and transforming those lines.

For a closer look at those processes see the full essay at “The Loan, the Witch, and the Market: Microfinance and the re-exploitation of women”.

Appendix A: Data and Scripts

The canonical versions of these files can be found at https://americancynic.net/log/2018/12/6/some_thoughts_on_kivas_interest_rates/#data

A.1. Data

The data used to generate the table and graphs presented in Section 1, “Two Misconceptions About Kiva” are available to download as:

-

active_partners.csv - the list of all active field partners with complete Portfolio Yield and Profitability data (as fetched using the Kiva API) in comma separated values format.

-

combined.csv - list of some chosen field partners data from both Kiva and the MIX Market (used to produce the figure correlating Kiva and MIX Market data). Unfortunately this is a hand-assembled file, and now that MIX Market data is not freely available, it can not easily be updated.

A.2. Scripts

The data files above can be automatically updated and the figures re-generated using the following scripts:

-

update-data.js - Node.js script which fetches field partner data from the Kiva API and writes

active_partners.csvto the working directory. (See package.json for its dependencies which can be installed with npm or Yarn.) -

analyze-all.r - R script which processes

active_partners.csvto generate the several Portfolio Yield ad Profitability graphics (in the current working directory) and outputs the summary table in AsciiDoc format. Requiresggplot2. -

analyze-correlation.r - R script which processes

combined.csvto produce the figure correlating Kiva and MIX Market data). Requiresggplot2andgridExtra.